10 Haunted City Parks in the USA

Parks mix nature, history, and the public’s imagination—perfect ingredients for ghost stories. Many U.S. parks were once battlefields, burial grounds, sites of tragedy, or early settlements. Old trees, fog, and empty benches create atmosphere; dim paths, ruins, and monuments provide storytellers with details; and local lore fills in the rest. Visiting a haunted park combines outdoor adventure with dark history and local culture. You can picnic, hike, bird-watch—and then swap ghost stories at dusk.

Central Park — New York City, New York

843 acres of lawns, lakes, winding paths, and secretive groves in the middle of Manhattan — is as much a landscape of stories and spirits as it is of trees and statues. Below are the park’s most persistent ghost stories, tragic histories, and creepy corners, organized by location and theme for easy reading or tour planning.

Belvedere Castle

Overview: A miniature stone castle overlooking Turtle Pond and the Ramble, built in 1869 as an ornamental structure.

Hauntings: Visitors and rangers report footsteps and a feeling of being watched inside the stone rooms after dark. The most common tale involves a late-19th-century park caretaker who allegedly remained after his time; cold spots and the smell of cigar smoke are often cited.

Tip: Best experienced at twilight while looking out over Turtle Pond — the castle’s silhouette and the layered city sounds create a cinematic backdrop.

The Ramble

Overview: A deliberately wild, densely planted woodland of winding paths designed for rambles and birdwatching.

Hauntings: The Ramble’s claustrophobic paths are the site of many disappearances and ghost stories, including a persistent legend of a woman in white seen walking or standing among the trees. Some say she’s searching for a lost child or lover; others tie the specter to suicides and crimes that occurred there over a century.

Tip: Daytime visits for birding and history; avoid lone late-night strolls — the Ramble’s atmosphere is uncanny after dark.

Sheep Meadow and The Mall

Overview: Open, grassy expanse (Sheep Meadow) and the tree-lined promenade known as The Mall, lined with elm trees and statues.

Hauntings: The Mall’s long promenade evokes Victorian promenades and has tales of ghostly 19th-century promenaders and children playing at dusk, with umbrellas and period dress seen faintly in peripheral vision. Some performers claim instruments play themselves near the Bethesda Terrace area.

Tip: Visit in the late afternoon for the interplay of light and shadow that fuels many of these sightings.

Bethesda Terrace and Fountain

Overview: The architectural centerpiece, with ornate stonework, a grand stair, and the Angel of the Waters statue overlooking the lake.

Hauntings: Reported phenomena include phantom music, crying, and apparitions on the stairways and under the arcade. Some accounts attach these to the many deaths and dramatic events along the lake and nearby paths.

Tip: The echoing arcade and mosaics make this a sensory spot — listen closely for unexplained sounds near closing time.

Wollman Rink Area

Overview: Ice-skating rink and surrounding lawns near the southern end of the park.

Hauntings: Skaters report last-minute chills, sudden candlelike lights, and occasional sensations of being pushed or tugged on the ice without a source. Stories sometimes reference the rink’s long winter history and past accidents.

Tip: Crowds dilute the uncanny; smaller groups skating near closing time report the most spine-tingling experiences.

Strangers’ Gate and the North Woods

Overview: The North Woods and bridle paths, more rugged than southern lawns, with rocky outcrops and secluded glens.

Hauntings: This area collects the darker folkloric detritus: sightings of hooded figures, distant calls, and the feeling of being followed. The name “Strangers’ Gate” feeds tales of transient spirits and travelers who never left.

Tip: Trek with a friend and a flashlight for night visits; during the day you’ll find hiking and birdlife.

Famous True Crimes and Tragedies That Fuel the Stories

Civil War and 19th-century deaths: The park’s creation required displacing small villages and burying old roads; historical dislocations plus 19th-century disease deaths and occasional violent crimes seed ghost lore.

Lucretia “Lucy” Brown (19th-century legends): Tales of lost women, murders, or suicides attached to unnamed women in white are common in oral tradition and feed sightings across the park.

Child deaths and drownings: Accidental drownings and wartime-era infant mortality contribute to recurring stories of children’s laughter or crying heard near the water after dark.

Prohibition and gangster-era violence: The Park’s secluded spots were used for secret meetings and

History: Opened in 1858, Central Park was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux. Over the 19th and early 20th centuries the park saw construction, reformatories, and burial grounds nearby.

Hauntings/paranormal activity: Reports include shadowy figures along the Ramble, a spectral woman on the Bethesda Terrace steps, phantom horse-drawn carriages, and disembodied voices. The park’s secluded paths and historic rock outcrops are common places for visitors and workers to feel sudden cold spots, watch orbs in photos, and witness figures that vanish when approached.

Lafayette Square — St. Louis, Missouri

Lafayette Square (often just “Lafayette”) is St. Louis’s oldest surviving urban public park, a pocket of Victorian-era charm surrounded by restored 19th-century homes, mansions, and brick rowhouses. Laid out in the 1830s and named for the Marquis de Lafayette, the park and its neighborhood chart the city’s growth, decline, and revival—and also carry a rich ledger of ghost stories and haunted reputations that draw paranormal visitors today.

Quick historical timeline

1827–1836: The area that would become Lafayette Square was part of the expanding city grid near the burgeoning riverfront economy. The square was officially set aside as public parkland in the 1830s.

1850s–1870s: Lafayette Square matured into one of St. Louis’s most fashionable residential neighborhoods. Grand Italianate, Second Empire, and Queen Anne homes rose around the park as wealthy merchants, professionals, and civic leaders built townhouses and mansions.

Civil War era: Like much of St. Louis, Lafayette Square felt the tensions of the Civil War. Missouri’s divided loyalties and military activity in and around the city touched the neighborhood—some historic homes were used for meetings and temporary housing.

Late 19th–early 20th century: The park became a focal point for civic life—bandstands, promenades, and public gatherings. Streetcar lines made the area accessible and stylish.

Mid 20th century decline: Economic downturns, suburban flight, and neglect hit Lafayette Square hard in the mid-1900s. Many houses were subdivided into apartments or left vacant; the park suffered decline and vandalism.

1970s–present: A major preservation and restoration movement revived the neighborhood. Blocks of restored Victorian homes, careful restoration of the park, and active neighborhood associations transformed Lafayette Square into a desirable historic district and cultural attraction.

Architecture and park features

The park itself is a roughly oval green with mature trees, walkways, statuary, and a central gazebo/bandstand—typical Victorian park planning meant for promenading and public concerts.

Surrounding the park are some of the best-preserved Victorian residential architectures in St. Louis: Italianate rowhouses, mansard-roofed Second Empire homes, and decorative Queen Anne façades.

Several notable buildings and local institutions have historical plaques or designations within the district; the area’s cohesive 19th-century streetscape is a major reason it’s protected and celebrated.

Why it’s popular with paranormal and dark-tourism visitors

Age and continuity: Many houses date to the 1850s–1880s and have long, layered histories—ideal soil for legends, tragedies, and lingering memories.

Civil War-era connections: The neighborhood’s 19th-century roots and wartime tensions supply a historical backdrop that fuels ghost lore.

Urban decline and violent episodes: Periods of abandonment and crime in the 20th century, plus stories of sudden deaths or domestic tragedies in old homes, often become focal points in oral histories and ghost lore.

Intact historic atmosphere: Restored gaslight-style lamps, brick sidewalks, and aged trees create a mood that helps stories stick and tours feel cinematic.

Notable hauntings and stories Note: As with all folklore, stories vary by teller and detail. Below are recurring legends and reports associated with Lafayette Square and nearby buildings.

The “Lady in White” of Lafayette Park

Story: Several park-goers and nearby residents claim sightings of a woman in a white dress gliding across pathways or standing beneath trees, particularly at dusk or during foggy nights. Accounts describe her as sorrowful but non-threatening; some say she vanishes near the park’s central gazebo.

Origins: Variations link her to a Victorian-era social tragedy—an unhappy engagement, a suicide, or sudden illness—that supposedly took place near the park. No single documented historical death has been conclusively tied to the apparition, but the image fits common “lady in white” motifs in American ghost lore.

Ghosts at the Lafayette Square Conservancy area homes

Story: Several restored townhouses and mansions report inexplicable phenomena: footsteps in empty rooms, objects moved, sudden cold spots, and lights switching on or off. Residents and tour guides occasionally recount strange smells (flower perfume or pipe tobacco) with no source.

Origins: These homes often have long resident lists; deaths, divorces, and wartime departures over a century-plus can create a patchwork of personal histories that fuel haunting claims. Some houses used as boarding rooms during the neighborhood’s decline reportedly had violent incidents—stories that migrated into modern haunt accounts.

Spring Grove Park — Cincinnati, Ohio

This nineteenth-century park encompasses landscaped grounds and a cemetery-like arboretum. It serves as both an active cemetery and a public arboretum, drawing historians, horticulturists, birders, and visitors who appreciate architecture and reflective landscapes.

Founding and early history

1845: Spring Grove was chartered by Cincinnati civic leaders and physicians who wanted a landscaped burial ground outside the crowded urban core. The cemetery was inspired by the rural cemetery movement, which began with Mount Auburn Cemetery in Boston (1831) and emphasized park-like settings, winding drives, picturesque plantings, and integrated artwork.

Landscape design: Initially laid out by architect Adolph Strauch, who joined in the 1850s and transformed Spring Grove into a model of the “park cemetery” ideal. Strauch removed fences between lots, created sweeping lawns, ponded the Mill Creek in places, and emphasized specimen trees and vistas. His vision balanced formal classical monuments with naturalistic plantings.

Expansion and arboretum development: Over decades Spring Grove acquired additional acreage and assembled one of the largest curated tree collections in the United States. The grounds now include formal gardens, fountains, ponds, and more than 1,200 varieties of trees and shrubs.

Architecture and monuments: The cemetery features notable mausolea, sculptural works, and chapels. Many prominent Cincinnati families and civic leaders are buried here — industrialists, politicians, artists, and veterans — making the site a repository of local history and genealogy.

Cultural and civic role

Public park function: From its earliest decades Spring Grove functioned as a public green space, hosting picnics, promenades, and later, guided walks, concerts, and horticultural events. Its role as an arboretum and a site for education continues today.

Notable burials: Among those interred are business leaders of Cincinnati’s 19th- and early-20th-century boom, military figures, artists, and reformers. The cemetery’s record-keeping and guided tours make it a draw for history buffs and genealogists.

Hauntings, ghost stories, and folklore Spring Grove’s size, age, and Victorian funerary art naturally invite ghost stories and local legends. While the cemetery is not as famously haunted as some urban supernatural hotspots, there are recurring themes in accounts and lore shared by visitors, tour guides, and local enthusiasts.

Common motifs

Spectral figures and apparitions: Several visitors have reported seeing solitary figures moving between monuments or along tree-lined drives, sometimes described as a woman in period dress, sometimes as a figure that fades when approached. These sightings often occur at dusk or under overcast skies, when long shadows and the cemetery’s formal statuary create an eerie stage.

Cold spots and sudden chills: Accounts describe sudden drops in temperature when standing near certain monuments or along shaded walkways. These are typical of many haunted-location stories and are often reported by people who combine night walks with ghost-hunting equipment.

Whispering and indistinct voices: Some visitors claim to hear whispers or murmuring when no one else is present. These reports usually come from people exploring quieter, wooded parts of the grounds away from main roads.

Unexplained lights and orbs: On evening visits, people have photographed unexplained spots of light or “orbs” over graves and along paths. Skeptics attribute these to insects, dust, lens flare, or camera settings, while believers interpret them as spiritual phenomena.

Specific tales and sites

The “Woman in White”: A recurring Spring Grove story involves a pale female apparition seen drifting near older family plots. Details vary: some accounts connect her to a young woman who died in the 19th century, others say she’s simply an unresolved presence tied to grief. The figure is most often reported near the older, tree-shaded sections of the cemetery.

Soldiers and veterans: Given the number of Civil War and other military burials, visitors sometimes report martial-sounding noises — drumbeats, marching, or distant cannon-like booms — on anniversary dates or early mornings. These sounds are typically anecdotal and part of local lore rather than documented phenomena.

Mausoleum activity: A few guides and visitors claim that certain mausolea seem to produce feelings of sadness, unease, or pressure. People who photograph mausolea at night have reported anomalies in images and a reluctance on the part of security to allow extended after-dark access

Grant Park — Chicago, Illinois

Grant Park — the “front lawn” of Chicago — sits along Lake Michigan between the Loop and the lakefront. Its open greens, grand monuments, museums, and festival grounds host millions of visitors each year. Beneath the formal landscaping and summer music festivals, Grant Park carries layers of Chicago history: landfill and lake reclamation, civic ambition, political spectacle, and, for those who listen, whispers of tragedy and the supernatural.

Brief historical overview

Early geography and development: Before European settlement the area was marshy lakeshore. In the 19th century, Chicago’s rapid growth demanded more usable land. Large-scale landfill projects pushed the shoreline east to create the lakefront that exists today. What is now Grant Park was once a combination of swamp, shoreline, and scattered small farms and estates.

“South Park” and early parks movement: In the mid-1800s the city began creating public green space. The area south of the central business district was designated for parkland, originally called South Park. The vision: a grand civic promenade to improve health, recreation, and the city’s image.

The naming and legal battles: For many years Chicago leaders debated private uses of the lakefront. By ordinance and lawsuit, the city protected the park as public space “forever open, clear and free.” In 1901 the park was renamed for Ulysses S. Grant. Over decades the park’s acreage was extended through landfill and the construction of drives, promenades, and cultural institutions.

Architectural and cultural growth: Important civic projects found a home in Grant Park: the Art Institute of Chicago (adjacent on the west), the Field Museum, Soldier Field, the Museum Campus nearby, and the Grant Park Music Festival and Taste of Chicago on its lawns. Monuments — including the Buckingham Fountain (1927) — became focal points. The park hosted political rallies, parades, and expositions that shaped Chicago’s public life.

Notable events and tragedies

Labor unrest and protests: The lakefront and adjacent park areas were stages for labor rallies and demonstrations during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Tensions between protesters and authorities sometimes turned violent.

Waterfront accidents: Before modern safety and lakefront design, drownings and boating accidents occurred along the shoreline. The creation of breakwaters and extensions shifted shoreline hazards, but tragedies did happen as Chicago grew.

Construction-related deaths: As landfill and major building projects reshaped the area, accidents occurred on docks, construction sites, and during heavy industrial work in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Hauntings and ghost stories Grant Park’s urban setting and long public use have given rise to a few recurring ghost stories and paranormal reports. These accounts are a mix of local lore, late-night thrill-seeker tales, and occasional first-person observations.

Soldiers and the war dead Story: On cool, foggy evenings some people say they see spectral soldiers marching near monuments and the older memorials around the park. The presence is usually described as distant footsteps, muffled commands, or a feeling of being watched near plaques and memorials honoring military service. Origins and context: Chicago has memorials and civic associations that honor veterans; the idea of soldierly apparitions is common at many civic parks with military monuments. No documented mass-casualty battlefield ties Grant Park itself to ghost soldiers, so these reports are likely atmospheric reactions to monuments, ceremonial rituals, and nighttime fog rolling off the lake.

The “Lady of Buckingham” Story: Buckingham Fountain, one of the park’s most famous landmarks, shines through steam and spray on summer evenings. Urban legend says a woman in white — sometimes described as a Victorian gown or a flowing summer dress — is seen lingering near the fountain after dark. Witnesses report a brief outline or the sensation of a presence, sometimes accompanied by a sudden chill. Origins and context: Romantic legends around fountains and water features are common: lost lovers, grief-stricken widows, or simply melancholy specters. Buckingham Fountain’s grandness and nighttime lighting make it an evocative setting for such tales. No historical record links a specific death at the fountain to the legend.

The vanished performer Story: During the early years when Grant Park hosted concerts and public entertainments, some tell of a tragic performer — a musician or singer — who collapsed or died during a performance. In modern retellings, solo strollers along the promenade sometimes hear snatches of an old melody, a phantom trumpet, or the echo of applause fading in the wind. Origins and context: Grant Park has long been a live-performance venue, and music’s strong association with the space fuels auditory haunt stories. The “phantom music” phenomenon is common in places with deep performing-arts histories; it often reflects memory and acoustics rather than

Jackson Park — Seattle, Washington

Built on land with Native American significance and early pioneer settlement, the park includes wooded trails and a small lake. Often called Jackson Park Golf Course — sits on Seattle’s Beacon Hill and has a layered history of land use, civic development, and stories that give it a slightly eerie local reputation. Below is a concise history followed by the hauntings, ghost stories, and local lore that have attached themselves to the park over the decades.

History

Indigenous land: The area that became Jackson Park was originally part of the traditional lands of the Duwamish people and other Coast Salish neighbors. Before urban development, it would have been a mix of forested slopes, wetland edges, and trails used for travel and seasonal resources.

Early 20th century development: As Seattle expanded, Beacon Hill became more settled. In the early 1900s the city acquired parcels of land for parks and public works. Jackson Park started to take shape as a public green space and eventually became developed into the municipal golf course most locals know today.

Jackson Park Golf Course: The golf course opened in the 1930s (with various improvements and redesigns over ensuing decades) and became a community focal point. The course layout, fairways, and trees have been shaped by several redesigns. Though municipal, it’s long been a neighborhood landmark where children played, couples strolled, and golfers flocked.

Mid-to-late 20th century changes: Like many urban parks, Jackson Park saw changing patterns of use, maintenance cycles, and city funding flows. Beacon Hill’s demographic shifts and urbanization influenced how the park was used — recreation, informal gatherings, community events, and occasional protests or memorials.

21st century: The course continues to operate as a public golf course and park space. It’s part of broader Beacon Hill life: nearby transit and development, community gardens, and neighborhood activism around open space and safety.

Hauntings, Ghost Stories, and Local Lore

Jackson Park has a quieter, more neighborhood-scale haunted reputation than some of Seattle’s more famous spooky sites. Its stories are often passed along by locals, teenagers, and golfers — short, anecdotal, and atmospheric rather than tied to a single famous tragedy.

“Shadows among the trees”

Story: Players and walkers sometimes report feeling watched or seeing something move just off the fairways at dusk — a fleeting dark shape between the tall pines and maples. People frequently describe the sensation of someone standing at the edge of the green who vanishes when you look directly.

Likely explanation: Dense tree lines, shifting light at sunset, and the natural startle response account for many sightings. Still, the setting — early evening, solitary fairways — fuels imaginations.

Whispered voices and distant laughter

Story: On late-evening visits, a few people have reported hearing faint, disembodied voices or laughter that seem to come from places where no one is visible — sometimes near the older stand of trees or by small drainage areas.

Likely explanation: Sound carries oddly in open parklands and can reflect off slopes and buildings. Wind through leaves and distant traffic can sound eerily like speech. The brain “fills in” ambiguous sounds into human voices, especially in low light.

The golfer who never finishes

Story: A widely shared anecdote among local golfers: an apparition of a solitary, old-fashioned golfer in outdated attire who appears on a fairway, taps a putt, and then is gone. Older players sometimes claim the figure wears clothing styles from mid-century decades.

Likely explanation: Costume details and era are usually reconstructed from memory. Players’ own golfing rituals and the sport’s tradition make the image of an eternal golfer stick in local storytelling.

Teen dares and park-at-night lore

Story: Like many urban parks, Jackson Park is a target for dares — midnight walks, “hold-my-breath” loops around the course, or racing the perimeter. These rituals generate their own short ghost tales: a hand that grabs your sleeve, a cold spot on the ninth hole, or a bench that creaks with an unseen sitter.

Likely explanation: Adrenaline, expectation, and peer influence create vivid experiences. The park’s nooks and benches are ideal staging points for spooky stories that spread quickly.

Rumors tied to Beacon Hill history

Story: Some accounts link sounds or apparitions at Jackson Park to broader Beacon Hill narratives — lost children, train or industrial accidents, or migrant hardships. These connections are often loose and more about neighborhood memory than verifiable events.

Likely explanation: Urban folklore often stitches together local historic hardships with present-day sensations. While the park has been a civic site rather than a place of major disaster, community memory preserves smaller personal tragedies that can feed ghost stories.

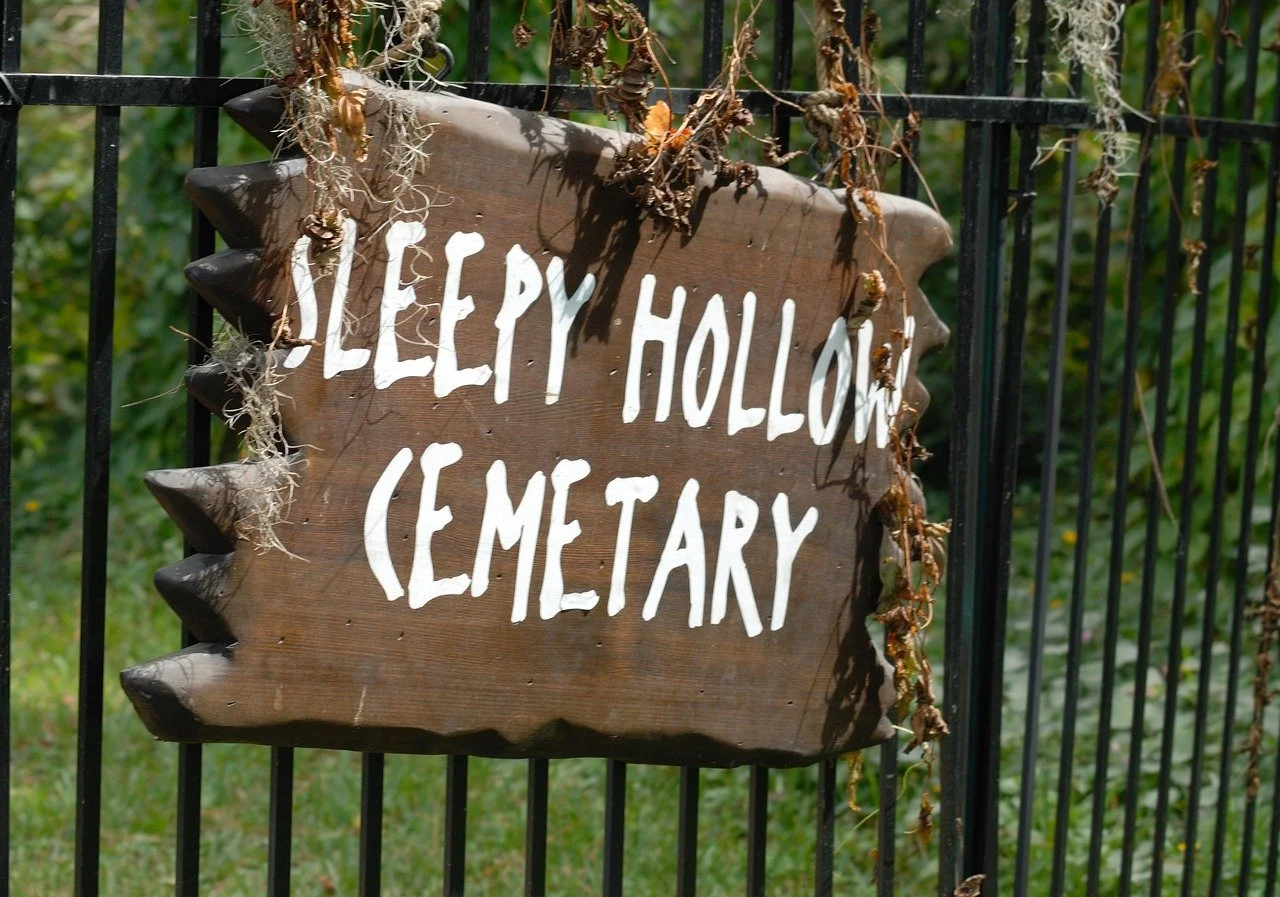

Sleepy Hollow Park — Sleepy Hollow, New York

The town’s park sits amid the legends of Washington Irving’s tale and 18th–19th century burial grounds. Sightings include a headless rider spelled out in local lore, fog-enshrouded horse hooves after midnight, and unexplained hoofprints in the grass. Visitors feel a heavy atmosphere and report hair-raising chills along the creek path.

Sleepy Hollow Park (commonly conflated with the village of Sleepy Hollow and the surrounding Sleepy Hollow Cemetery and Rockefeller State Park Preserve) sits along the eastern Hudson River in Westchester County, New York. The area’s history blends early Dutch colonial settlement, Revolutionary War action, Gilded Age country estates, and — perhaps most famously — the literary and folkloric legacy of Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” That mix created fertile ground for ghost stories, hauntings, and a modern culture of dark tourism.

Quick historical overview

Indigenous and early colonial period: Before European arrival the area was inhabited by Lenape peoples. Dutch settlers arrived in the 17th century, establishing farms and small villages along the Hudson. The Dutch name for the general region included terms like “Tarrytown” and references to hollows and sloping land along the river.

18th century and Revolutionary War: The Sleepy Hollow area (then often called North Tarrytown) sat near strategic points on the Hudson. Local troops and skirmishes occurred across Westchester County; militia activity and occupation by both British and American forces left their marks on the landscape and local memory.

Washington Irving and literary fame (early 19th century): Washington Irving published “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” in 1820 as part of The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. Irving’s vision of a secluded, superstitious hollow populated by the Headless Horseman turned the area into an enduring fictional landscape. Irving himself lived at Sunnyside, a Rhinebeck estate across the river from Sleepy Hollow, but his story fixated popular imagination on the Sleepy Hollow/Tarrytown locale.

19th–20th centuries: The area developed as a suburban and riverfront community. Wealthy New Yorkers built country estates nearby; one of the most famous local sites later became the Rockefeller family’s holdings and, eventually, public parkland and preserves.

Sleepy Hollow Cemetery and Sunnyside: Sleepy Hollow Cemetery (originally Tarrytown Cemetery, incorporated in 1849) became a Victorian rural cemetery with winding lanes, mature trees, and notable interments (including Washington Irving himself). Sunnyside, Irving’s home, and other historic houses add to the cultural landscape visitors come to see.

Modern parklands and preservation: Parts of the former estate lands and riverfront tracts around Sleepy Hollow now fall under municipal parks, Sleepy Hollow Cemetery’s grounds, and Rockefeller State Park Preserve. These open spaces preserve Hudson River views, woodlands, wetlands, walking trails, and the atmospheric settings that inspired stories.

Why the place feels haunted

Landscape and atmosphere: The low-lying, tree-draped hollow, dense woods, old stone walls, and river fogs create classic spooky ambiance. In the 19th century, rural cemeteries were designed as picturesque, melancholy landscapes—ideal for superstition and storytelling.

Literary association: Irving’s story gave names and images (Ichabod Crane, Katrina Van Tassel, Brom Bones, and the Headless Horseman) that anchor every creak and wind gust to a narrative of restless spirits. Once a site becomes linked to a famous ghost story, visitors interpret ordinary things as paranormal.

Tangled history: Colonial-era deaths, Revolutionary War casualties, and later family tragedies are woven into local lore; people like to imagine these histories producing lingering presences.

Notable hauntings and ghost stories

The Headless Horseman: The single most famous “resident” of Sleepy Hollow is Washington Irving’s Headless Horseman, said to be the ghost of a Hessian soldier decapitated by a cannonball during the Revolutionary War. Folklore places him galloping the roads at night in search of his missing head. Modern retellings embellish sightings near the Old Dutch Church, along the Pocantico River, and around Sleepy Hollow Cemetery.

Ichabod Crane sightings: Some local tales claim that Ichabod Crane’s spirit — the superstitious schoolmaster from Irving’s tale — wanders near the cemetery and along the old carriage roads. These sightings are typically part of living storytelling during Halloween tours rather than independent eyewitness reports.

The Old Dutch Church and Sleepy Hollow Cemetery: The Old Dutch Church (built in the late 17th/early 18th century with later repairs and restorations) and its cemetery are central to Sleepy Hollow mythology. Visitors report cold spots, sudden gusts, and a strong feeling of being watched near certain headstones. The cemetery contains graves of Revolutionary War veterans and 19th-century notables; its funerary art and mausoleums feed ghost stories. Irving’s own grave is here, which draws pilgrimages and more tales of spectral presence.

Congress Park — Saratoga Springs, New York

Dating to the 19th-century resort boom, the park near mineral springs and bathhouses carries ghost stories of lost guests and performers. A 15-acre emerald heart in Saratoga Springs, New York, it sits where high society, mineral springs, and the macabre intersect. Laid out in the 19th century on the site of the city’s famed springs, the park is part public greenspace, part cultural memory: fountains, grottos, sculptures, the Canfield Casino nearby, and winding paths that have watched generations promenade, protest, celebrate — and sometimes whisper about ghosts.

Quick context and timeline

Early use (pre-1810s): Indigenous peoples used the area for its mineral springs long before European settlement. The springs’ reputation for healing set the stage for Saratoga’s rise as a resort.

1810s–1840s: Saratoga’s springs became a fashionable destination. Hotels, bathhouses, and promenades clustered around the water.

1860s–1870s: The land that is now Congress Park officially developed into a landscaped public park. Victorian-era landscaping, ornamental ponds, terraces, and walkways were added.

Late 19th century: The Canfield Casino (now owned by the Saratoga Springs Preservation Foundation) and adjoining resort architecture anchored the park as a center of leisure, gambling, and social life.

20th century to present: Park improvements, historic preservation, and cultural events made Congress Park a civic focal point. The park’s antique structures and century-old trees preserve the echoes of past eras.

Key features that set the scene

The springs and fountains: Sculptural fountains and ornate ironwork rim the spring areas. The Old Iron Spring and the Geyser Spring are among the features that drew visitors for decades.

Canfield Casino and Congress Hall: Elegant 19th-century buildings that framed the social life of the resort era. They anchor ghost stories because of their proximity to the most active historical sites.

The grove, terraces, and footbridges: Intimate, shadowed spots where fog and lamplight can easily turn atmosphere into suggestion.

Statues and monuments: Figures that stand watch over the park and feed local lore (any statue can look like it moved at the wrong hour).

Why Congress Park breeds stories

Intersection of leisure and tragedy: Resorts attract large, transient crowds. With heavy drinking, gambling, affairs, and dramatic social swings, the stage was set for scandal and sometimes death — ideal ingredients for ghost lore.

Long memory and tourism marketing: Saratoga’s identity as a historic resort encourages storytelling. Locals and guides embellish tales to entertain visitors, and the park’s antiquity invites speculation.

Visual atmosphere: Victorian architecture, ironwork, fog over the springs, and night lighting make ambiguous sights and sounds easier to interpret as something supernatural.

Notable hauntings, legends, and ghost stories

The Lady in White

Story: Several versions circulate. The most common describes a woman in a white dress seen gliding along the park paths or sitting near the springs at dusk. She’s sometimes said to be searching for a lost lover or mourning a child.

Origins & variations: No single documented death matches every telling; like many “Lady in White” legends, it likely amalgamates multiple tragedies: drownings, sudden illness, or jilted women from the resort era. Sightings are usually at twilight or on foggy mornings.

The Gambler’s Shadow (Casino/Canfield area)

Story: Spectral footsteps and shadowy figures are reported near the old Canfield Casino and Congress Hall. Some visitors and employees claim to hear whispers and the clink of chips when the buildings are empty.

Origins & context: The casino’s history of high-stakes gambling and social rivalry supplies an easy narrative: lost fortunes, angry rivalries, and occasional violence. These stories often center on late-night sounds and the sense of being watched in former gambling rooms.

Children at the Springs

Story: Playful, echoing laughter or the soft sound of running feet near ponds and rockwork has been reported, especially by people walking alone at dawn or dusk. Some hear small voices near the grottoes and stonework.

Possible roots: Child mortality rates were higher in the 19th century; playgrounds and promenades historically saw more families. The sensation of children playing where none are visible is a common motif in hauntings tied to old parks.

The Steamboat Scent and Phantom Music

Story: On certain evenings people say they smell coal smoke or river steam that shouldn’t be there, or they hear strains of 19th-century dance music drifting through the trees.

Likely explanation: Memory and atmosphere. The park used to vibrate with bandstands, orchestras, and the constant motion of resort life. The brain can translate ambiguous ambient sounds into recognizable

White Point Garden — Charleston, South Carolina

White Point Garden sits at the southern tip of the Charleston peninsula where the Ashley and Cooper Rivers meet to form the harbor. A public park since the 18th century, its leafy lawns, antebellum ironwork, and strategic location have made it a central site for military history, civic memory, and, of course, ghost stories. The park is a compact, atmospheric place: live oaks dripping with Spanish moss, historic cannons and monuments, and the waterfront promenade that frames Charleston’s maritime past.

Historical highlights

Colonial and Revolutionary era: The point has been a defensive and public space since Charleston’s earliest days. In the 18th century, the area around White Point served as a common gathering place and as part of the city’s coastal defenses.

19th century and antebellum use: As Charleston grew wealthier, the point (then known sometimes as The Battery extension) became a fashionable promenade. Wealthy residents built nearby mansions; the park became an element of the city’s civic landscape.

Civil War and military significance: During the Civil War, Charleston was a major Confederate port and target. The park area functioned in a defensive capacity; artillery pieces and fortifications were located nearby. After the war, White Point became home to various memorials and monuments honoring Confederate soldiers and other historical figures.

Monuments and memorials: The park contains a number of statues, cannons, and commemorative plaques — including several Confederate monuments and guns captured in historic conflicts — reflecting Charleston’s layered, contested memory of war and seafaring history.

20th century to present: The park has been maintained as a public green space, a gathering spot for festivals and events, and a scenic vantage point for harbor views. Ongoing debates about the appropriateness and placement of Confederate monuments have shaped public discussion about the site in recent decades.

Physical features to notice

Live oak trees draped in Spanish moss—these give the park its signature Southern Gothic mood, especially at dusk.

Rows of historic cannon and artillery from various periods.

Multiple memorials and statuary referencing naval and Confederate history.

The waterfront promenade that looks out over Charleston Harbor, Fort Sumter, and the shipping channels.

White Point Garden’s long history, military associations, and location by the water have made it fertile ground for local ghost lore. Stories tend to cluster around wartime echoes, grief-laden apparitions, and the atmospheric setting of moss-draped oaks and quiet benches after dark.

Common themes in the hauntings

Soldiers and Confederate apparitions: Given the park’s ties to Civil War memory and displayed artillery, many accounts describe phantom soldiers — often in period uniforms — who appear briefly among the trees or march into the fog and vanish. Witnesses report feeling a chill, seeing a figure dissolve into the mist, or glimpsing a face in a uniform that looks “old-fashioned” and distant.

Phantom cannon sounds and unexplained bangs: Some visitors and locals say they’ve heard muffled booms, clinks, or the distant sound of cannon fire at night with no source. These auditory experiences are often attributed to lingering echoes of wartime trauma or the park’s proximity to historic battle sites like Fort Sumter.

The grieving woman: Several versions of a classic Southern ghost tale circulate about a woman in period dress who sits on a bench or walks the promenade, sometimes near the water, sometimes beneath a particular live oak. She is described as melancholy, waiting, or searching — often thought to be a woman who lost a loved one in the war or to the sea.

Children’s laughter and phantom play: On quieter nights, some visitors report the sound of children playing or laughing where no children are visible. These sounds are sometimes linked to the park’s long use as a public recreation space and the idea of old lives layered into the landscape.

Waterfront phantoms and sailors: Because White Point faces the harbor, stories also involve sailors or fishermen who vanish into the fog, or bottles and items appearing on the shore that cannot be explained. Some link these to the many shipwrecks and maritime tragedies along the coast.

Notable local reports and lore

Bench apparitions: Several storytellers claim a specific bench in the park is frequented by a spectral woman. Accounts vary in detail but tend to agree that she appears at dusk and sometimes disappears when approached.

Fogged figures near cannons: Visitors have reported seeing a figure in military garb near one of the park’s cannons, standing motionless and then dissolving into sea mist. These sightings are usually fleeting and accompanied by a sudden drop in temperature.

Sensory experiences more than full apparitions: Many contemporary reports emphasize smells (gunpowder or salt air), sudden cold

City Park (Pozieres Park area) — New Orleans, Louisiana

City Park, one of the oldest and largest urban parks in the United States, occupies more than 1,300 acres of live oaks, lagoons, sculpture gardens, and winding paths in Uptown New Orleans. The Pozieres Park area sits within City Park’s northeastern reaches, near the Fate/City Park Avenue corridors and close to the park’s more secluded groves. Its layered history blends Indigenous land use, colonial and antebellum landscapes, public recreation development, and the long, complicated social history of New Orleans — all set against a backdrop of water, moss-draped oaks, and frequent flooding. That mix makes City Park, and pockets like Pozieres Park, ripe for folklore, eerie tales, and reports of strange occurrences.

A brief historical overview

Pre-colonial and colonial era: Before European settlement the land that became City Park lay along Native American hunting and fishing grounds in the Mississippi floodplain. French and Spanish colonial land grants and plantations later parceled the area. The trees, marshes, and bayous shaped how the land was used and later preserved.

19th century public park development: The City of New Orleans acquired much of the land in the 1850s and 1860s. Formal plans for City Park date from the 1850s; landscape architects and municipal leaders saw a public park as civic improvement similar to those in northern cities. The park’s oaks, many centuries old, became a defining visual feature.

Pozieres Park name and military memory: The name Pozieres has military resonance; it echoes the World War I battlefield of Pozieres Ridge in France, where many New Orleans soldiers fought. Local naming and memorialization in the early 20th century honored those service members. Portions of City Park were dedicated or renamed to commemorate local veterans and wartime sacrifices, a pattern that shaped park toponyms, monuments, and memorial groves.

20th century expansions and attractions: Over decades City Park grew and added attractions — the New Orleans Museum of Art and Sculpture Garden, the Botanical Garden, Storyland, the Carousel, golf courses, and sports fields. The park also became a site for New Orleans culture: festivals, Second Line parades, and everyday neighborhood life.

Modern era, hurricanes, and recovery: City Park repeatedly bore hurricane damage, most massively from Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Katrina flooded vast sections of the park, damaged trees and historic structures, and shifted the character of many spaces. Recovery efforts revived the park but also amplified stories of loss, displacement, and memory.

Why City Park feels haunted

Age and atmosphere: The park’s ancient live oaks, Spanish moss, and shadowy lagoons create a liminal, timeless environment that naturally fuels ghost stories.

Layers of human activity: As a place of funerary memory, wartime commemoration, leisure, and tragedy (drownings, storms, accidents), City Park accumulates narratives of grief and remembrance — fertile soil for hauntings.

Isolation and acoustics: At night the park becomes isolated; sounds carry oddly across water and mossy branches, producing unexplained creaks, whispers, and the impression of footsteps where none should be.

Notable hauntings and ghost stories associated with City Park and Pozieres Park area

The Weeping Woman / Mourning Matron: Several versions circulate of a white-clad woman seen near lagoons and shaded pathways. She’s sometimes described as a maternal figure searching for lost children or mourning a buried loved one. Witnesses describe the figure as translucent in car headlights or as a reflection in still water. Such apparitions are common folkloric motifs — here connected to the park’s history of loss and child-play areas (like Storyland) that emphasize family memory.

The Soldier of Pozieres: Tied to the area’s military naming, some visitors report seeing a solitary uniformed soldier walking among the oaks at dusk, shoulder-sagged, as if carrying memories of combat. This figure is interpreted as a veteran who died far from home or who never found repose after World War I. The soldier sometimes appears near plaques or memorial plantings, then fades among the roots and moss.

Phantom Children at Storyland and lagoons: Storyland and nearby picnic areas draw many tales of disembodied giggling, the sound of children at play when the park is otherwise empty, and fleeting glimpses of small figures between trees. These stories double as both haunting and sentimental remembrance: imagined children linked to playgrounds, drownings, or parents separated from children during storms and emergencies.

The Lady of the Oaks: A recurring City Park tale describes a woman who walks beneath a particularly ancient oak, pausing to place her hand on the trunk. Witnesses

Alamo Square Park — San Francisco, California

Perched on a gentle hill in San Francisco’s Western Addition, Alamo Square Park is best known for its postcard-ready row of Victorian houses called the Painted Ladies. But beneath the pastel facades and the tourist selfies lies a layered history: indigenous land, a military fortification, a civic green space, and a neighborhood that survived fires, redevelopment, and social change. Along the way it picked up a handful of ghost stories and eerie local lore.

Brief historical timeline

Pre-contact and early settlement: The area that became Alamo Square was originally Ohlone land. Spanish colonization and later Mexican control reshaped land use across the peninsula.

Mid-19th century: As San Francisco boomed after the Gold Rush, the hill was used for military and defensive purposes. The name “Alamo” reportedly comes from a stand of cottonwood (alamo in Spanish) trees that once grew nearby, though some local accounts tie it to the Alamo in Texas by sentimental or veteran associations.

1860s–1890s: Residential development took off. Stately Victorian and Edwardian homes were built on and around the hill; the row now called the Painted Ladies was completed in the late 1800s. The area became a desirable middle- and upper-class neighborhood.

1906 earthquake and fire: The quake and subsequent fires damaged much of San Francisco; Alamo Square suffered but many structures survived or were rebuilt, which is why the Victorians remain relatively intact.

20th century: The neighborhood experienced decline mid-century, with waves of urban renewal, redlining, and social change. Alamo Square Park itself was renovated and became an important public space and community focal point.

Late 20th–21st century: Gentrification and preservation efforts restored many homes and boosted the area’s visibility. The Painted Ladies became an international icon after being featured in films and television.

What makes the place special

Architecture: A concentration of well-preserved Victorian and Edwardian homes — especially the Painted Ladies — makes Alamo Square one of San Francisco’s most photographed views.

Civic function: The park has long served as a public gathering place — for recreation, protests, picnics, and citywide events — anchoring the neighborhood socially as well as geographically.

Layered stories: From indigenous history to Gold Rush wealth, wartime fears, natural disaster recovery, and modern urban change, Alamo Square compresses much of San Francisco’s story into a compact hilltop.

Hauntings, ghost stories, and local lore Alamo Square doesn’t have the violent, headline-grabbing ghost legends of Alcatraz or the Presidio, but it does carry quieter spectral tales and atmospheric folklore tied to its old houses, the park at dusk, and the city’s layered past.

Victorian echoes in the homes: Several owners and neighborhood residents have reported hearing the kinds of sounds you’d expect in very old houses: footsteps in empty rooms, muffled voices late at night, the creak of floorboards as if occupied by former inhabitants. These are most commonly recounted by tenants in older Victorian flats and by caretakers during late-night maintenance. Locals tend to interpret these as the presence of past residents whose routines still imprint on the houses.

The Painted Ladies’ presence: The Painted Ladies themselves attract romanticized ghost talk — sightings of a woman in period dress on the upstairs porches, or the feeling of being observed while taking photos at dusk. Reports are anecdotal and intermittent; many stem from the powerful visual and emotional pull those houses exert, especially on foggy evenings when gaslight-like streetlamps glow.

Park-at-dusk melancholy and “watchers”: Some visitors to Alamo Square Park report an odd stillness at twilight, followed by the sense of being watched. A handful of people claim they’ve seen shadowy figures glide across the far lawns or along the tree line, vanishing when approached. These experiences often coincide with fog rolling through the city, which heightens the mood and interprets everyday silhouettes as something more mysterious.

Children’s laughter with no children in sight: There are stories of hearing distant playful children’s laughter or faint games from parts of the park where no one is visible. These sounds are sometimes tied to the memory of families who lived nearby in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, or to the many children who once played on those lawns before urban change thinned local populations.

Storm hauntings and earthquake memories: Given San Francisco’s seismic past, some locals say the city retains the echo of the 1906 earthquake — low, rumbling sounds or a trembling sensation when none should occur. While there’s no clear supernatural claim, the sensation is often described in language used for hauntings (cold spots, pressure changes), blending geological memory with ghost lore.

Plan a spooky, history-soaked road trip visiting haunted city parks across the United States. Each stop blends local lore, spectral sightings, verdant scenery, and accessible urban amenities. Ideal for ghost-hunters who love culture, food, music, and short walks between eerie hotspots……you will definitely have a great time!

Make this beautiful day count!

Annette