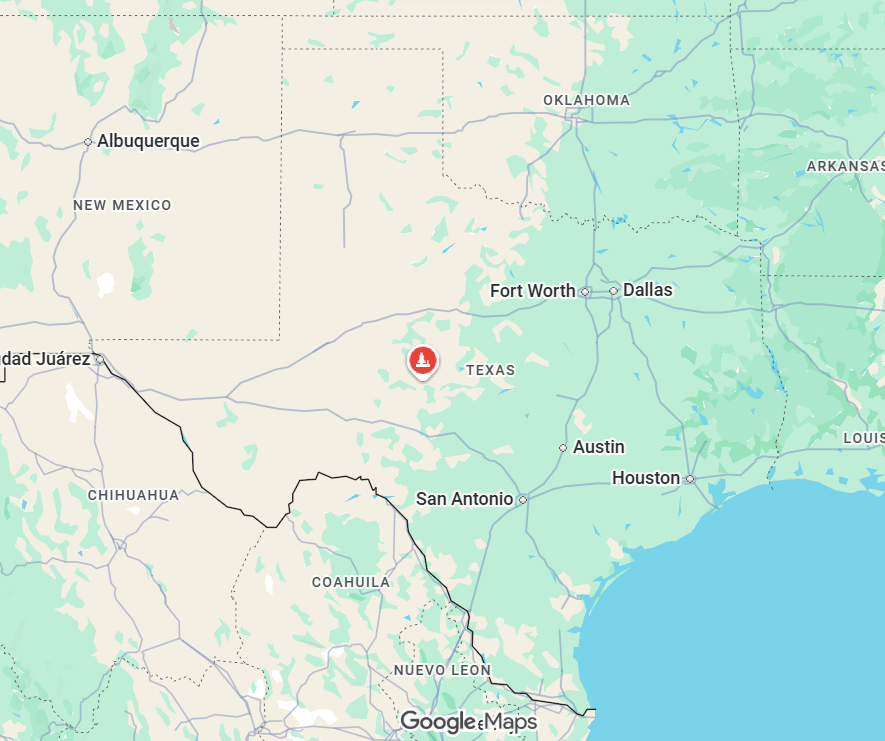

27 Fascinating Ghost Towns in Texas

Texas Ghost Towns — A Spooky, Soulful Experience for Curious Travelers

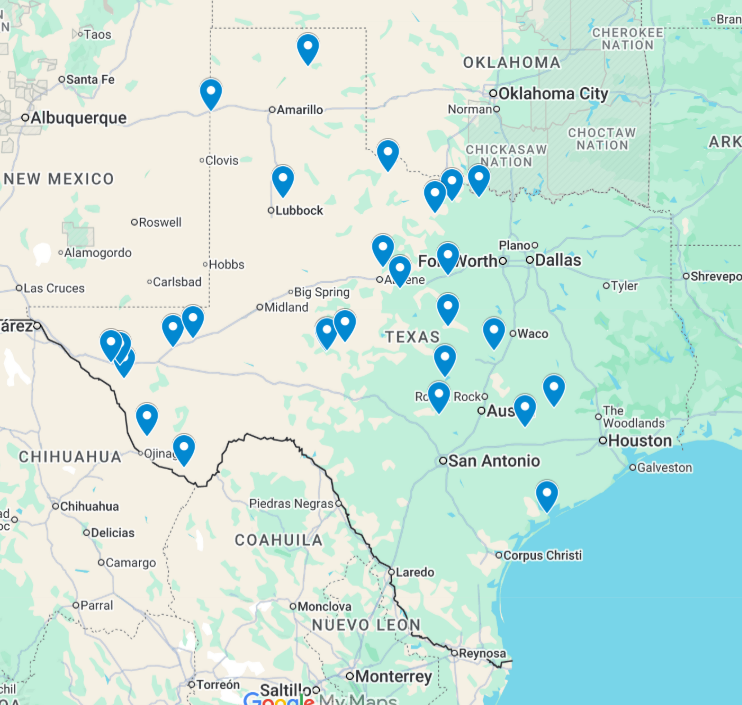

Texas ghost towns are equal parts history, mystery, and photo-ready decay. Ideal for history lovers, paranormal fans, photographers, and anyone who enjoys experiences over stuff….Texas ghost towns have a lot to offer for those who choose to seek them out. Some of the towns listed still have residents living there albeit not many, while others have nothing more than a lone cemetery with whispers of the life the town once held.

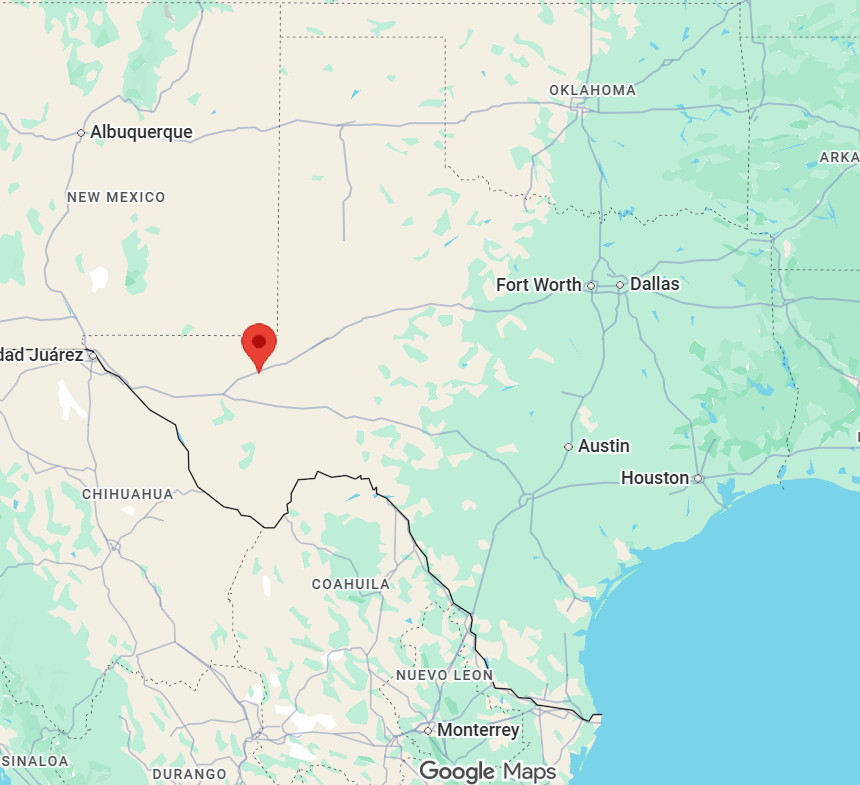

Terlingua — Once a mercury-mining camp near Big Bend, now a quirky ghost town with ruins, adobe buildings, and an artsy vibe. A famous mining town near Big Bend that boomed in the early 1900s due to the Chisos Mining Company. It is now a popular tourist destination known for its abandoned church and ruins. Its story is one of boom-and-bust mining, frontier grit, and creative reinvention — shifting from a rough mining town to a magnet for artists, adventurers, and ghost hunters.

The Mining Boom (1880s–1940s)

The modern history of Terlingua begins with the discovery of cinnabar (mercury ore) in the late 19th century. Mercury, used in gold and silver processing, was a valuable commodity. In the 1890s–1920s, a small but intense mining industry grew. Major operations included the Chisos Mining Company and the Terlingua Mining Company. The town’s population swelled as miners, their families, and supporting businesses arrived. Terlingua became famous for its quicksilver (mercury) production. Ore was roasted in furnaces to extract mercury, creating dramatic smoke and a grimy, industrial atmosphere. Life in mining Terlingua was rugged. Company housing, commissaries, and basic services clustered near the mills. The town had diverse residents, including Mexican and Mexican-American workers, Anglo miners, and others—reflecting the broader cultural intersections of West Texas borderlands. The boom was never easy: ore quality fluctuated, transportation was difficult, and living conditions were harsh.

Terlingua Cemetery during Dia de Los Muertos

Me at the Old Perry School

Decline and Abandonment (1940s–1960s)

By the 1940s, several factors led to decline: falling mercury prices, depleted ore, and changing industrial practices reduced demand. World War II temporarily boosted resource needs, but the long-term trend was downward. The mills closed, jobs vanished, and many residents left. Buildings deteriorated; parts of Terlingua became a ghost town. Environmental impacts from mercury processing lingered, leaving tailings and contamination around the mills — a reminder of the town’s industrial past.

Rebirth: Artists, Outlaws, and Free Spirits (1960s–1980s)

In the 1960s and 1970s, Terlingua drew a new kind of settler: artists, bohemians, hippies, and adventurers seeking solitude and cheap land. The striking desert landscape, dramatic skies, and ruins offered inspiration and a place to live outside mainstream society. Adventurers and off-grid types set up homes, studios, and small businesses. Some restored old structures; others built eclectic dwellings from salvage. Terlingua’s reputation as an offbeat community grew. Visitors were drawn to its ghost-town ruins, desert beauty, and proximity to Big Bend.

Church of Santa Inez / Saint Agnes Church

Ruins in Terlingua

Chili Cook-off and Tourism (1967–present)

In 1967, the first Terlingua International Chili Championship (often called the Terlingua Chili Cook-off) was held, originally as a fundraiser to save a local cemetery and later as a celebration of chili culture. The event exploded in popularity and helped put Terlingua on the map for tourists. The cook-off became an annual tradition, attracting thousands of chili teams and spectators. It contributed to Terlingua’s identity as a quirky, community-driven destination. Tourism tied to Big Bend National Park, ghost-town tours, hiking, stargazing, and the cook-off helped stabilize the local economy. Small businesses—restaurants, lodgings, guide services, and galleries—cater to visitors seeking rugged natural beauty and alternative culture.

Modern Terlingua: Living History and Dark Tourism

Today, Terlingua is a patchwork: a handful of permanent residents, seasonal visitors, artists, and business owners who embrace the town’s wild character. The old cinnabar mills and mining ruins remain focal points for history-minded visitors and photographers. The Ghost Town area (Old Terlingua) still contains adobe and stone ruins, the remnants of processing furnaces, and a cemetery with weathered markers. It’s a draw for history buffs and paranormal enthusiasts alike. Terlingua occupies a unique niche in American tourism: part historic mining town, part artistic outpost, part desert retreat, and part dark-tourism site. Visitors come for the landscape, the history, the weirdness, and the community events like the chili cook-off and

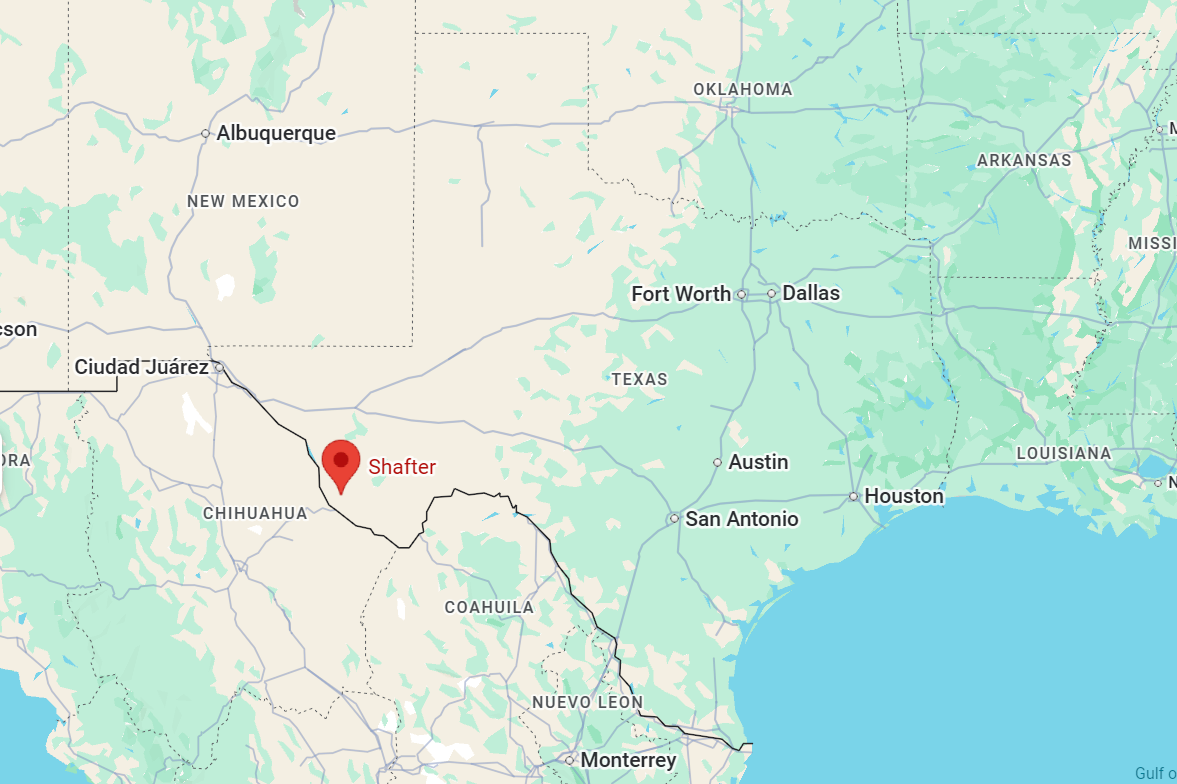

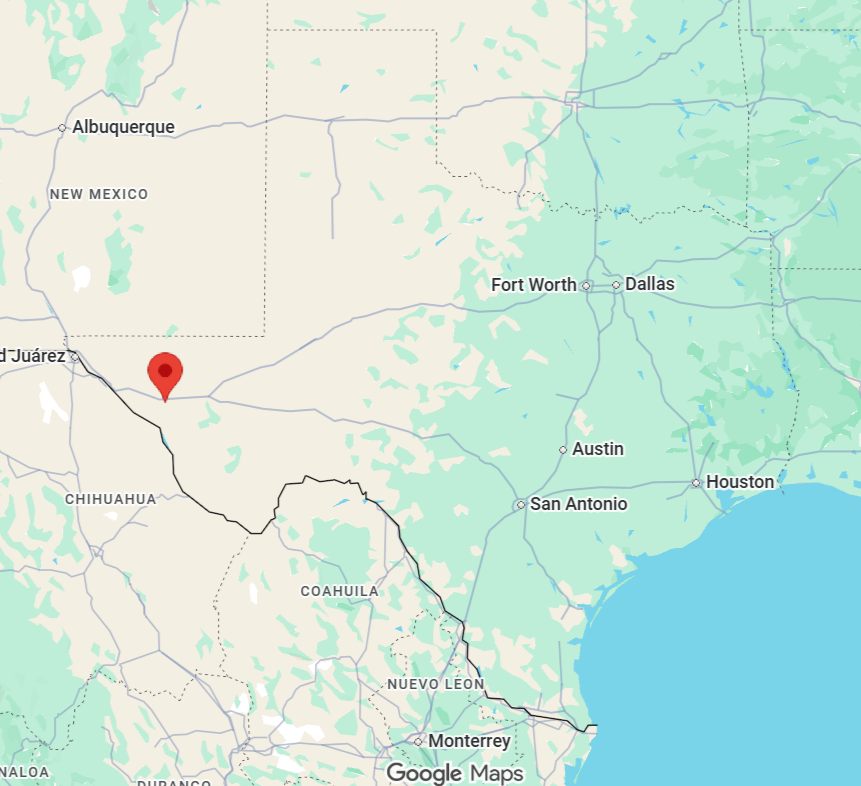

Shafter — a small West Texas community with roots in ranching, railroads, and mining — has a history that reflects the broader patterns of settlement, industry, and decline that shaped the region.

Origins and early settlement

Before European settlement: The area around present-day Shafter was part of the vast plains used seasonally by Indigenous peoples, including Comanche bands and other Plains groups who hunted and moved through the region. 19th-century ranching: Following Texas statehood and the post-Civil War cattle boom, the region developed as open range. Large ranches and trails crossed the area, and ranching remained the economic base into the early 20th century.

Railroad and town founding

Arrival of the railroad: The expansion of railroads in West Texas in the late 19th and early 20th centuries established new shipping points and towns. Shafter grew up as a station and shipping point along local rail lines that connected ranching communities to markets. Naming: The community took the name Shafter in honor of General William R. Shafter, a U.S. Army officer notable for his service in the Spanish–American War (1898). Naming towns after military figures was common in that era and signaled ties to national events and pride.

Mining and economic shifts

Lead and silver mining (Trans-Pecos region connection): While Shafter, Texas itself is not the famous Shafter mining district of Presidio County, the name and mining-era boom-and-bust experience in West Texas communities are often linked in local memory. West Texas mining booms — particularly for silver, lead, and later other minerals — reshaped several towns during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Shafter-area economies were affected by commodity cycles, nearby mining activity, and fluctuating demand for ranching products. Agriculture and oil: Beyond ranching, small-scale agriculture and, where discovered, oil exploration influenced local fortunes across West Texas. Communities like Shafter adapted to seasonal and market-driven changes, with some growth tied to nearby discoveries or transport improvements.

20th century: roads, depopulation, and consolidation

Improved roads and automobiles: The rise of automobile travel and better roads changed settlement patterns. Small rail-dependent towns often declined as people and commerce consolidated in larger county seats and highway towns. School consolidation and services: Like many rural Texas communities, Shafter saw services—schools, post offices, stores—close or consolidate as populations fell or shifted to larger towns. These changes reflected broader rural depopulation in the 20th century. Military and wartime impacts: World Wars and national service drew young people away temporarily or permanently; wartime demand sometimes gave local agricultural producers short-term booms.

Present-day Shafter

Small, rural community: Today Shafter exists as a quiet, sparsely populated West Texas locale. It retains vestiges of its past in building sites, ranch fences, and the landscape shaped by grazing and transport routes. Cultural landscape: The community is part of the broader cultural tapestry of West Texas—ranching traditions, local cemeteries and churches, and a lifestyle tied to land stewardship and neighbor networks. Heritage and memory: For residents and descendants, Shafter’s history lives in family stories, land records, and regional histories that document how railroads, ranches, and economic change shaped daily life.

Old service station in Lobo

More ruins in Lobo

Lobo — a tiny settlement with a big, lonely presence on the West Texas plains — is a classic example of the boom-and-bust towns that sprang up and faded across the American frontier. Located in southwestern Culberson County, near the New Mexico border, Lobo’s history is short, stark, and tied to ranching, railroads, and the challenges of desert life.

Origins and early years

Settlement began in the late 19th and very early 20th centuries as ranching spread across the Trans-Pecos region. The area’s sparse water and harsh climate limited large-scale settlement, but it suited wide-open cattle and sheep ranches. The name "Lobo" comes from the Spanish word for "wolf," likely referencing coyotes or the lone-wolf nature of the outpost. Spanish and Mexican place-names are common in West Texas, reflecting the region’s earlier history.

Railroad and post office

Lobo gained a foothold as a small railroad stop and service point. The rise of rail lines through West Texas gave many isolated ranching communities brief lifelines: a way to ship livestock, receive supplies, and connect to markets. A post office was established in the early 20th century, an important marker of a recognized community. Post offices often defined a town’s official existence on maps and in government records.

Economic life

Ranching — cattle and sheep — was the backbone of Lobo’s economy. The wide, arid plains supported grazing but required mobility and large land holdings. Small businesses that typically accompanied ranch communities—general stores, a feed supplier, blacksmithing services—would have existed at modest scale when population warranted.

Decline and desertion

Like many West Texas settlements, Lobo never grew into a substantial town. Its geographic isolation, limited water sources, and competition from larger nearby towns prevented major growth. Changes in transportation (decline of small railroad stops, improved highways concentrating trade in larger towns), consolidation of ranch lands, and rural depopulation in the 20th century all contributed to Lobo’s decline. Eventually the post office closed and the population dwindled to near-zero. Today Lobo is considered a ghost town or near-ghost town, with few if any permanent residents and only remnants of buildings or foundations at the site.

Visiting

Expect remote, rugged travel conditions; bring water, fuel, and a high-clearance vehicle. Many ghost towns in West Texas are on private ranch land—respect property boundaries and seek permission when required. Photographers and history buffs will find stark landscapes, weathered structures (if any remain), and a sense of the vast open West that inspired cowboy and frontier lore.

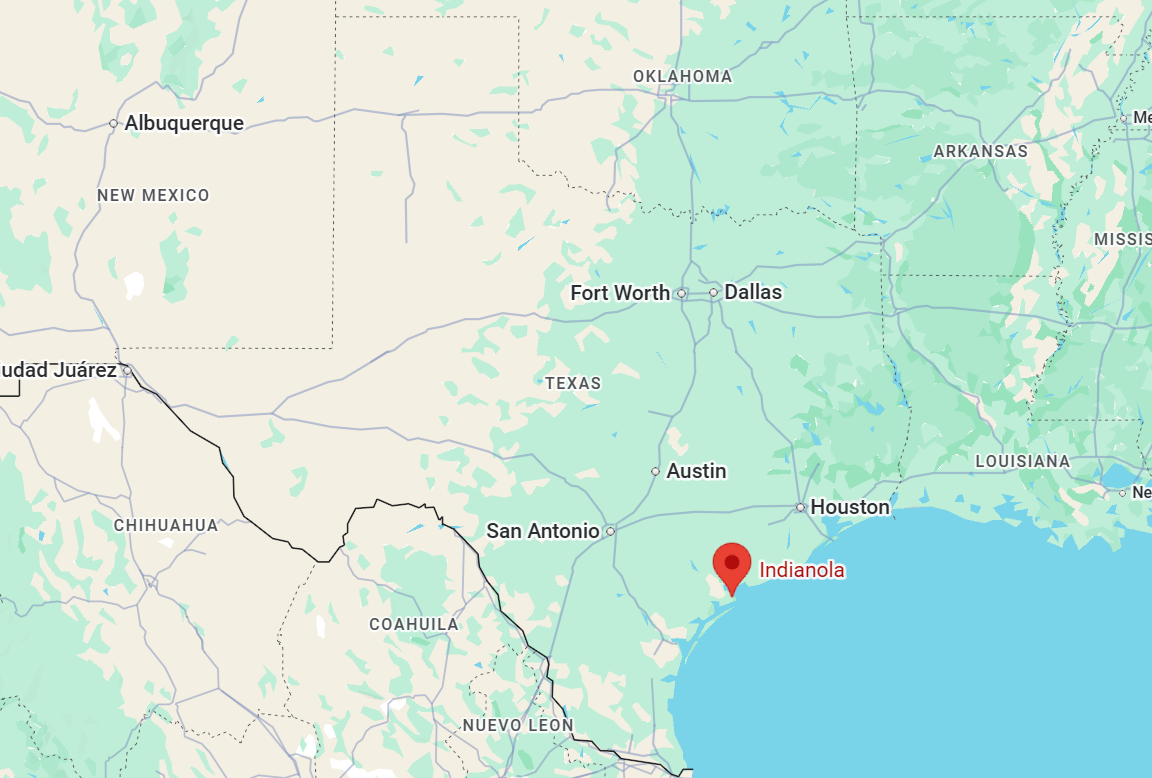

Indianola — Once a major Gulf port near Matagorda, destroyed by two catastrophic hurricanes (1875, 1886). All that remains are a few foundations, markers, and a cemetery on the island—really evocative of lost coastal towns. Once a major port city on Matagorda Bay, it was destroyed by two devastating hurricanes in 1875 and 1886.

Early settlement and founding

Before Euro-American settlement, the area around Matagorda Bay was home to Karankawa and other Native American groups who fished, hunted, and navigated the coastal estuaries. In the 1830s, as Texas separated from Mexico and later became a republic, entrepreneurs and settlers looked for Gulf ports to serve the new republic. Forts and towns grew along the coast to support trade and immigration. Indianola began in the 1840s as a small settlement called Indian Point. It was renamed Indianola in 1846 when the U.S. Army established a presence, and the name likely honored the many Native Americans who had frequented the area.

A rising port and immigration gateway (1840s–1870s)

Indianola’s deepwater anchorage on Matagorda Bay and its location opposite the barrier islands made it an attractive port for shipping, cotton exports, and passenger traffic. In 1849 the U.S. Army established Forts on Matagorda Bay, and Indianola became the port of embarkation for troops and supplies supporting frontier forts and campaigns. The 1850s–1870s were the town’s golden age. Indianola was a primary Texas port of entry for European immigrants, particularly Germans and Irish. Steamship lines ran regular service between Galveston, Indianola, and ports to the east. The town developed streets, wharves, warehouses, hotels, and a lively commercial district. It served as a regional center for trade, immigration processing, and shipping cotton and other commodities. During the Civil War Indianola was a strategic Confederate port, later occupied by Union forces. After the war, it continued to rebuild and grow.

County seat and cultural life

Indianola became the county seat of Calhoun County and hosted courts, offices, and civic life. Churches, schools, and social institutions marked it as an established coastal town. The port’s international shipping links brought cultural diversity. German immigrants left a strong imprint on local culture and farming in the surrounding county.

The hurricanes and decline (1875, 1886)

Indianola’s fortunes were overturned by severe storms. In September 1875 a powerful hurricane struck Matagorda Bay. The storm surge and winds destroyed much of Indianola’s waterfront, wiped out the wharves, and sank many ships. The town suffered massive building damage and loss of life. Residents rebuilt after 1875; government and private investment restored the port, and the town briefly regained its role. In August 1886 another catastrophic hurricane — arguably the deadliest blow — struck Indianola. A massive storm surge inundated the town, which had been partially rebuilt on the same low-lying site. The surge demolished structures, wrecked the railroad depot, and buried sections of town. Reports estimate hundreds of fatalities overall from the storm and massive property loss. After 1886 the town never recovered. Ship lines and commerce shifted to other ports, notably Galveston and ports further along the coast. Businesses and residents relocated rather than rebuild in a place so clearly vulnerable.

Ghost town and legacy

By the 1890s Indianola had effectively ceased to exist as a functioning port. The county seat moved and civic functions ended. Many of Indianola’s abandoned buildings and remaining artifacts were scavenged or left to decay. Nature reclaimed much of the site; coastal erosion, shifting sands, and vegetation covered remnants. In the 20th and 21st centuries the Indianola site became part of public lands and historical preservation efforts. A state-run historical site and markers commemorate the town’s past. Foundations, bits of bricks, and cemetery plots remain as archaeological traces. Indianola’s story is remembered as a cautionary tale about coastal vulnerability and as a chapter in Texas immigration and trade history. It stands as an evocative example of how environmental forces can erase even thriving human settlements.

Indian Creek — a quiet ribbon of land and water with roots in Indigenous presence, frontier settlement, and rural Texas life — has a local history that reflects broader patterns in East and Central Texas: Native American use, Anglo settlement, agriculture and ranching, small-community institutions, and gradual change through the 20th century.

Early inhabitants and Indigenous presence

Long before Anglo settlers arrived, the lands around the creek were used seasonally and year-round by Indigenous peoples. Tribes and bands associated with the Caddoan-speaking groups, and later the Hasinai and other groups within the broader Southeastern cultural sphere, used waterways like Indian Creek for fishing, hunting, and travel. The creek’s name itself preserves that memory of Indigenous presence, though the specific tribes tied to a given “Indian Creek” locale can vary by county across Texas.

Arrival of European-American settlers (mid-1800s)

Anglo-American settlers began arriving in increasing numbers in the decades after Texas independence (1836) and statehood (1845). Indian Creek areas typically attracted settlers because creeks provided reliable water for homesteads, livestock, and mills. Early settlers cleared land for small farms and established basic infrastructures: log cabins, fence lines, and small fields for corn, cotton, and cattle pasture. In many Indian Creek communities, families of Anglo, German, and sometimes other European origins established homesteads. These farms were often worked with family labor and, prior to the Civil War, in some regions with enslaved labor.

Agriculture, mills, and local economy (late 19th century)

Indian Creek’s economy in the late 1800s centered on subsistence and cash-crop agriculture, cattle, and local processing. Where the creek’s flow was sufficiently strong, settlers built gristmills or sawmills to process grain and timber—critical services that helped small settlements grow into local hubs. Cotton became a dominant cash crop in many Texas creek valleys. Cotton gins and small general stores often formed the nucleus of rural commerce. Local churches and schoolhouses were typically among the first permanent communal buildings erected.

Community institutions and daily life (turn of the century)

One-room schoolhouses, Baptist or Methodist churches, and fraternal lodges helped create community identity. Social life revolved around seasonal rhythms (harvest, planting), religious observances, and events like quilting bees, fish fries, and school recitals. Families relied on creek water and wells; crossing and fording creeks was part of travel. Dirt roads and horse or wagon transport connected Indian Creek settlements to nearby towns and county seats.

20th-century changes: roads, electricity, and mechanization

The arrival of better roads and later paved highways altered settlement patterns. Mechanized farming and improved agricultural technology reduced the need for farm labor, prompting migration to towns and cities. Rural electrification in the 1930s–1940s transformed domestic life, bringing electric lights, refrigeration, and radio. Telephone service gradually expanded, knitting rural residents into wider social and economic networks. Some Indian Creek areas experienced out-migration during the Dust Bowl and Great Depression eras, while New Deal programs and wartime demand brought cycles of change and occasional growth.

Preservation of local memory

Historic churches, cemeteries, mill ruins, and schoolhouse foundations often survive as tangible links to the past. County historical commissions, local genealogists, and long-time residents contribute to preserving and documenting the microhistories of places called Indian Creek. Oral histories—stories of floods, pioneer hardships, marriage celebrations, and schoolteachers—are crucial for understanding day-to-day life beyond census data and land records.

Thurber — Coal-mining company town near the Palo Pinto–Erath county line. Industrial ruins, brick structures, and the ghostly remains of a company store reflect its once-thriving status. Once one of the largest coal-mining towns in Texas, it rose quickly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and then largely vanished when economic and technological shifts made its mines and company-town model obsolete.

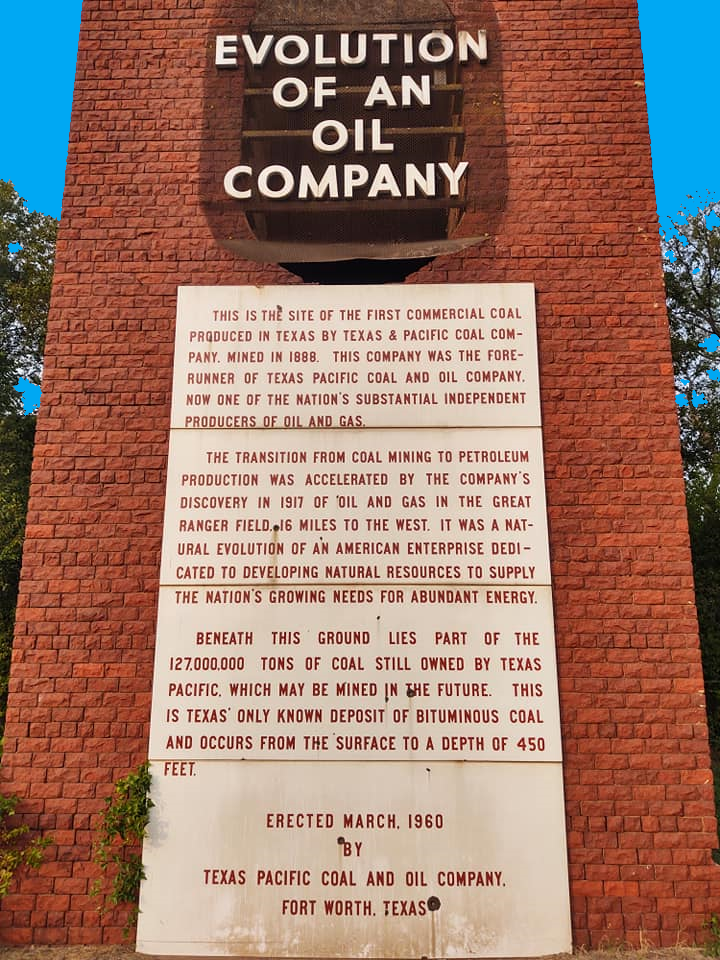

Founding and Growth (1880s–1910s)

The town grew up around bituminous coal deposits discovered in the late 19th century. Coal was in demand for railroads and industry, and the Texas & Pacific Railway helped open the area. In 1886 the Texas & Pacific and several entrepreneurs established mines. By the 1890s large operations were under way. Organizers created Thurber as a classic company town. Coal companies (notably the Texas Pacific Coal Company and later the Texas Pacific Coal & Oil Company) owned housing, stores, schools, a post office, a hospital, and church facilities. The town’s layout and services were designed to serve miners and their families. At its peak in the 1910s and 1920s Thurber’s population reached an estimated 8,000–10,000 people, making it one of the largest towns in North Texas at the time.

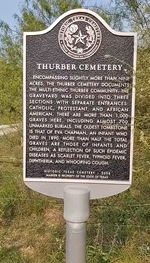

Ethnic Diversity and Culture

Thurber was notable for its ethnic mix. The coal companies recruited immigrant laborers—Italians, Poles, Lithuanians, Mexicans, African Americans, and others—creating a multicultural mining community. Ethnic neighborhoods, mutual aid societies, social clubs, and separate churches and schools reflected both the diversity and the social segmentation common in company towns. The town had a lively cultural scene for a mining camp: sporting events, band concerts, dances, and ethnic festivals. Miners and their families built a resilient, community-oriented culture tied to the rhythms of the mines.

Labor and Conflict

Labor unrest and union organizing were part of Thurber’s story. Miners experienced long hours, hazardous conditions, wage disputes, and company control of many aspects of life. Although the major nationwide strikes of the coal industry did not always mirror in Thurber, tensions over wages and working conditions persisted. Company influence over housing, stores, and employment complicated labor relations.

Economic Decline and Transition (1920s–1930s)

Several forces undercut Thurber’s prosperity. The railroads and industries began switching from coal to oil and natural gas for fuel. Deeper and more expensive mines, the depletion of high-quality seams, and competition reduced profitability. Mechanization and changes in mining technology reduced the need for large numbers of miners. By the late 1920s and into the 1930s the major mining companies began closing operations and selling off assets. The company-town model unraveled. Gradually many residents left in search of work elsewhere; buildings were dismantled or moved. Thurber shifted from a bustling mining hub to a much-smaller, sparsely populated area.

Visiting Thurber Today

Visitors encounter a rural setting marked by concrete foundations, brick chimneys, and mine waste piles. Weathered structures and interpretive markers at times hint at the town’s busy past. Thurber appeals to history buffs, urban explorers, and those interested in industrial archaeology, immigration history, and the built environment of company towns. It also attracts paranormal and ghost-tourism interest—wrapping its abandoned buildings and layered past in an aura that invites storytelling.

Thurber is a snapshot of a transformative period in American industrial history: rapid extraction-based growth, heavy reliance on immigrant labor, a paternalistic company-town system, and a rapid decline when energy and technology changed. The town’s multicultural roots and the lives of its miners add human depth.

Fort Phantom Hill: Located near present-day Abilene in Taylor County, Texas, was a short-lived but strategically significant U.S. Army outpost on the Texas frontier. Established in late 1851 and abandoned permanently by 1854, the fort’s history reflects the challenges of frontier military logistics, tensions with Native American tribes, and the turbulent settlement patterns that shaped mid-19th century Texas. Technically it may not be a ghost town on its own but it has all the makings for a ghost town.

Founding and Purpose

In response to ongoing raids and conflicts between Plains Indian groups and settlers and to protect developing frontier roads, the U.S. Army established a line of forts across Texas in the 1840s–1850s. Fort Phantom Hill was one of these frontier posts, intended to protect emigrant routes, deter raids, and assert federal authority in the region. The post was officially established in November 1851 under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Henry E. Williamson of the 2nd U.S. Dragoons. It was named for a nearby sandstone butte—Phantom Hill—whose shape and mirage-like appearance inspired the name.

Location and Layout

The fort sat on the upper Plain of the Brazos River drainage in what was then sparsely settled country. The site was chosen for perceived control over the surrounding plains and proximity to travel routes, but it suffered from poor water quality and scarcity. Construction used adobe and local stone. Typical structures included officers’ quarters, enlisted barracks, a hospital, storehouses, and defensive works, arranged around a parade ground. Construction was hurried and often incomplete, reflecting supply and labor difficulties.

Daily Life and Challenges

Soldiers at Fort Phantom Hill faced extreme isolation, supply shortages, poor water, disease, and harsh weather. These conditions made garrison life difficult and undermined the post’s long-term viability. Relations with Native American tribes in the region were tense. The fort’s presence was intended to project military power and discourage raids, but limited manpower and resources constrained active operations.

Short Operational Life and Abandonment

Fort Phantom Hill’s active use by the U.S. Army was brief. By 1854, after only a few years of operation, the post was deemed unsustainable due to its poor location, lack of reliable water, and the expense of supply. The Army abandoned the fort that year as part of a broader reorganization of frontier defenses. After abandonment, the site passed through various uses. Settlers scavenged building materials. During and after the Civil War, the fort became a local landmark and occasional shelter but never regained its status as an active military post.

Later History and Preservation

Over decades the fort’s ruins and the Phantom Hill butte became a visible relic of the frontier era. Local interest in the site grew as historians and antiquarians documented the remains. In the 20th century, Fort Phantom Hill became the focus of archaeological and historical study. Excavations and surveys recovered artifacts and clarified the layout and daily life at the post. The site is now recognized for its historical significance as part of the story of westward expansion and military efforts to secure the Texas frontier. Interpretive markers and preservation efforts help visitors understand the fort’s short but illustrative role.

Visiting Today

The site is accessible to those traveling in the Abilene area and appeals to history buffs, dark tourism seekers, and those intrigued by frontier ruins and landscapes. The lonely butte and scattered foundations evoke the hardships and transient nature of many frontier posts. For travelers interested in paranormal or atmospheric experiences, Fort Phantom Hill’s ruins and the stark surrounding plains make an evocative stop—quiet, windswept, and steeped in the stories of soldiers, settlers, and the land they sought to control.

Mertzon — small, weathered, and full of West Texas stories — sits as the county seat of Irion County, roughly midway between San Angelo and Fort Stockton. Its history reflects the patterns of ranching, railroad ambitions, oil booms, and the stubborn endurance of rural communities on the South Plains.

Founding and early settlement

The land that became Irion County was long part of Comancheria and later frontier grazing territory. Anglo-American settlement increased after the Civil War as Texas ranching expanded westward. Irion County was created by the Texas Legislature in 1889, named for State Senator Robert Anderson Irion. For several years the county had no organized government or permanent seat. Mertzon emerged in the 1890s as the community centered around land owned by the Mert Zorn family (sometimes reported as a contraction of Mert Zorn), and nearby ranching operations. The town was initially known as "Mertson" in some records before standardizing as Mertzon.

County seat and civic life

In 1901 Mertzon was designated the county seat of Irion County, a role that anchored its civic identity despite a small population. The county courthouse and related services drew residents and commerce from the surrounding ranches. Early economy: ranching (cattle and sheep) dominated. The town functioned as a supply and trade point for ranch families and seasonal cowboys, with general stores, a post office, schools, churches, and social halls forming the core of community life. The Mertzon courthouse and public buildings went through adaptations over the decades; they have been symbolic landmarks for the county seat’s continuity.

Railroad plans and limitations

Unlike many Texas towns that boomed with the arrival of a railroad, Mertzon never became a major rail junction. Railroad routes in West Texas more often favored larger nearby towns, which helped those communities grow more rapidly. The absence of major rail infrastructure kept Mertzon small and oriented toward local ranching rather than large-scale commerce or manufacturing.

Oil, highways, and midcentury change

Oil exploration in West Texas in the 20th century affected the region unevenly. While nearby regions saw larger booms, Irion County and Mertzon experienced smaller-scale oil and gas activities that provided periodic economic boosts and jobs. The development of highways and greater automobile access changed life patterns. State roads connected Mertzon to larger markets and services, but also made it easier for younger residents to move away for work and education.

Historic sites and landmarks

Irion County Courthouse: As with many small Texas counties, the courthouse is a central historic and civic feature. Ranching landscapes and historic ranch homes: the open country around Mertzon preserves the cattle- and sheep-ranching legacy that shaped daily life for generations. Small-town architecture: vintage storefronts, churches, and school buildings capture a century-plus of local history.

Modern era and identity

Today Mertzon remains small but resilient. It serves as the administrative heart of Irion County and a service hub for ranchers and residents across a wide rural area. The town’s character—quiet, practical, tied to land and tradition—appeals to visitors seeking an authentic slice of West Texas life: big skies, wide ranchlands, and close-knit community rhythms. For travelers interested in history, ranch culture, or dark-sky stargazing, Mertzon and its surroundings offer straightforward, unvarnished experiences that contrast with Texas’s urban centers.

Van Horn — small town, big sky, crossroads of West Texas history. Nestled along Interstate 10 in Culberson County, Van Horn sits between the Davis Mountains and the Chihuahua Desert, and its history reflects frontier settlement, railroad expansion, ranching, mining, and strategic transportation. Here’s a concise yet textured history of Van Horn.

Origins and name

The area that became Van Horn was long used by Indigenous peoples, including Apache groups and earlier inhabitants who traveled the desert and mountain corridors. The town is named for James Judson Van Horn, an early settler and rancher in the region. He established a ranching presence in the late 19th century and served as postmaster when the community gained postal recognition. The first post office called “Van Horn” was established in 1884, marking the name’s official use.

Railroad and town founding

The pivotal moment for Van Horn came with railroad development. In the 1880s and 1890s, rail lines across West Texas opened new economic and settlement opportunities. The Southern Pacific Railroad (and earlier railroad interests that would become part of larger lines) drove growth by making the town a stop between the larger hubs of El Paso and points east. As a railroad stop and service point, Van Horn grew as a supply and shipping center for ranchers and miners in the surrounding region.

Ranching, mining, and frontier economy

Ranching dominated early local economy. The wide open spaces of the Trans-Pecos were home to large cattle operations; Van Horn served as a trade and shipment point for livestock and supplies. Mining and mineral prospects in the broader region (including limestone, gypsum, and other resources) influenced periodic economic activity, though Van Horn remained more of a ranching and transport hub than a mining boomtown.

20th century — highways, military, and modern change

The rise of automobile travel and the development of highways reinforced Van Horn’s role as a waypoint. U.S. Highway 80 and later Interstate 10 placed the town on a major east–west corridor across the southern U.S. During World War II and the Cold War era, the region’s remoteness and open space made parts of West Texas important for military training and aerospace testing. Nearby facilities and the broad desert contributed to strategic use of the area, though Van Horn itself remained primarily civilian. In the mid-20th century, the community maintained schools, churches, small businesses, and services catering to travelers and local families. Population remained small and steady; Van Horn served as county seat of Culberson County.

Recent decades — film, astronomy, and space

Van Horn and its surroundings have periodically drawn filmmakers and artists looking for dramatic desert backdrops and authentic West Texas atmosphere. The region’s dark skies and open landscape have attracted astronomy enthusiasts. More recently, West Texas has become a focus for private spaceflight development; while the major launch sites are centered elsewhere in the region, proximity to remote desert and transportation corridors gives Van Horn strategic interest for supporting industries and travelers connected to aerospace activities.

Points of historic interest

Old railroad-era structures and sites tied to early ranching and the post office mark the town’s 19th- and early-20th-century roots. Local cemeteries and historic markers tell stories of settlers, ranchers, and travelers who shaped the area. The county courthouse in nearby Van Horn is part of the civic history of Culberson County.

Today Van Horn is a small, resilient town that serves interstate travelers, supports local ranching and small-business life, and appeals to visitors interested in West Texas landscapes, history, and dark-sky viewing. Its location makes it a convenient stop for cross-country road trips, and its quiet, remote setting offers a taste of classic Trans-Pecos life.

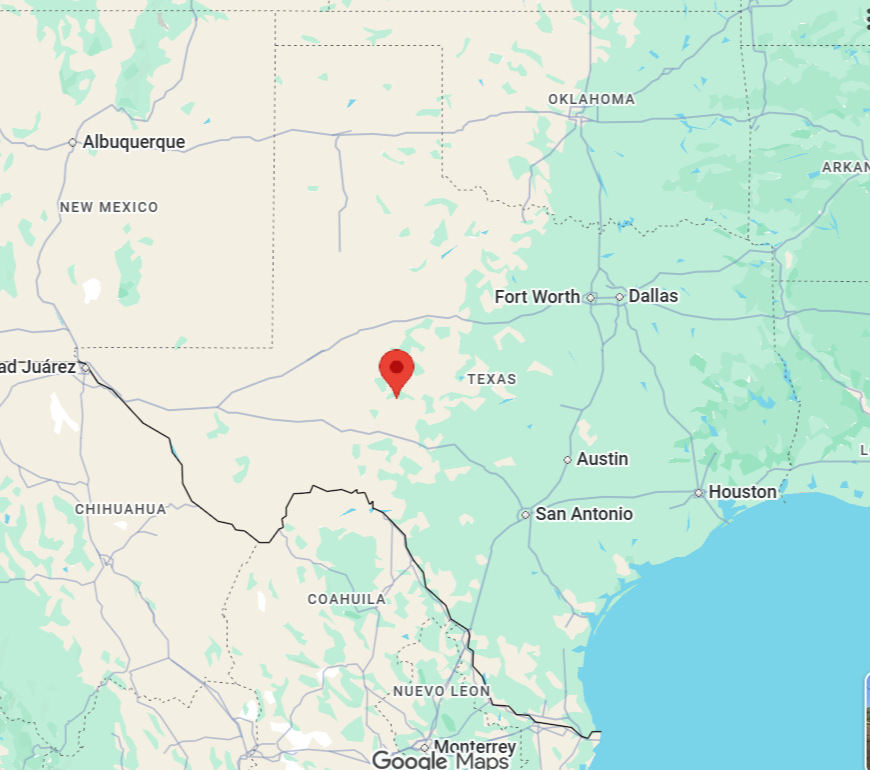

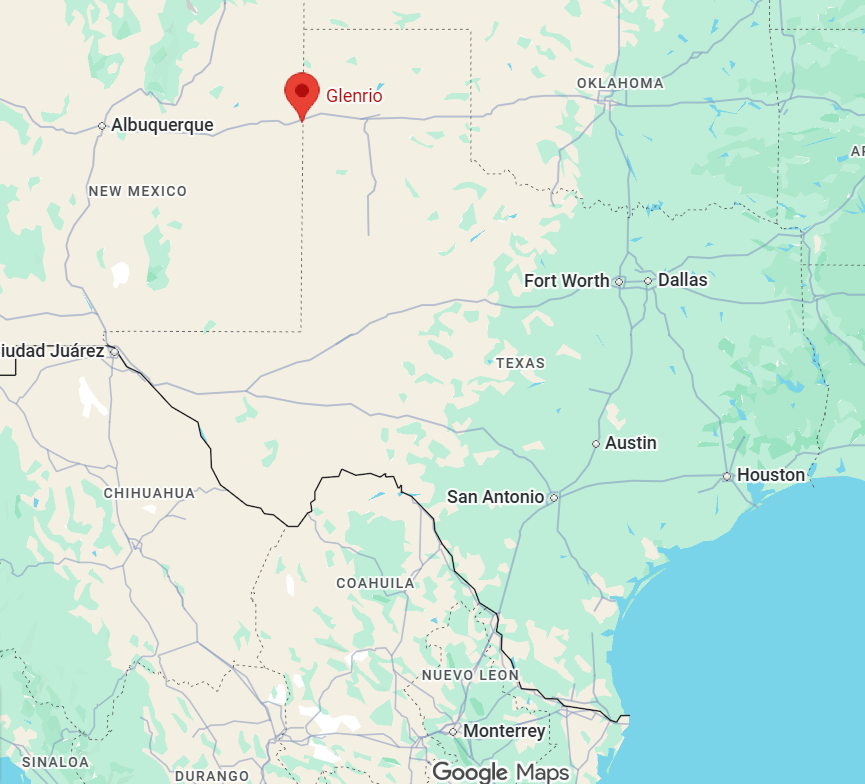

Glenrio — a town that exists in a peculiar in-between — sits on the Texas-New Mexico line and is one of the most evocative relics of Route 66 culture. Its history is a patchwork of cattle trails, railroad ambitions, highway boom-and-bust cycles, and borderline ingenuity. Here’s the story, trimmed to the bones and served with a dash of desert dust.

Founding and early days

The area that became Glenrio was originally part of open range grazing and cattle country in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Sparse water and wide horizons defined life here. The community’s name is sometimes said to come from combining “glen” (a small valley) and “rio” (Spanish for river), though the site is essentially desert scrub with only intermittent washes rather than a true river.

Railroad era

Glenrio’s first significant growth came with the arrival of the Santa Fe Railroad in the early 1900s. A rail siding and stop spurred modest settlement: a handful of businesses, homes, and services for travelers and railway workers. The railroad established Glenrio as a practical stop on long west-east routes across the Plains and into the Southwest, setting the pattern of a small service-oriented community.

Route 66 and the boom

The defining chapter for Glenrio began in the 1920s and 1930s as the federal highway system took shape. When Route 66 was established in 1926, it passed directly through Glenrio. The town’s location on the route between Amarillo and Tucumcari made it a natural stopping point for travelers. During the 1930s–1950s, motels, cafés, gas stations, and tourist courts sprang up to serve cross-country motorists. Glenrio became known for both its practical services and its role as a cultural boundary — businesses on the New Mexico side sometimes stayed open on different schedules than those on the Texas side due to differing state laws (notably liquor regulations in earlier decades). Roadside architecture and neon signs created the visual language of midcentury Americana. Motor courts, vintage gas pumps, diner counters and novelty signage defined Glenrio’s look.

Decline with the Interstate

The opening of Interstate 40 in the late 1950s–early 1960s began to route traffic away from Route 66. Bypasses and faster alignments meant fewer travelers stopped in small towns like Glenrio. By the 1970s and 1980s, traffic had dwindled severely. Businesses closed, buildings were abandoned, and many structures fell into disrepair. The town’s population evaporated; Glenrio became a near-ghost town, frozen in a midcentury moment.

Ruins, preservation, and cultural afterlife

Today Glenrio is celebrated by Route 66 enthusiasts, photographers, and fans of roadside Americana. Some of the best-known remnants include an old motel façade, several service-station shells, a boarded-up café, and neon skeletons that recall the town’s heyday. Preservationists and historians have worked intermittently to document Glenrio’s structures and history. The town’s remains are valued for their authenticity: they illustrate the life cycle of American highway towns and the visual culture of midcentury travel. Glenrio’s location on the state line gives it a quirky fame. The state boundary cuts through the main road; you can stand in two states at once while taking in rusting signage and wind-swept tumbleweeds.

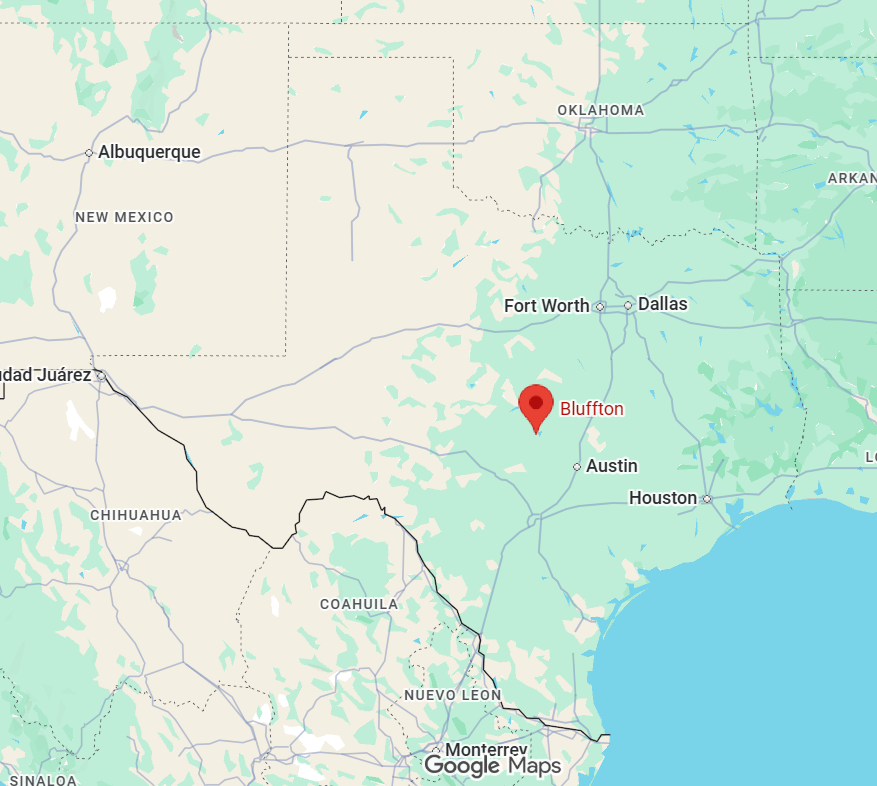

Old Bluffton — This town was abandoned in 1937 for the construction of Buchanan Dam and is usually submerged under Lake Buchanan. A small, weathered community with roots deep in North Texas frontier life — began as a 19th-century settlement shaped by rivers, ranching, and the slow push of settlers across the plains.

Founding and early growth

Settlement period: Old Bluffton was established in the mid-1800s as Anglo-American settlers moved west from older East Texas and Southern states. The town’s location near water sources and along early wagon and cattle-driving routes made it a natural stopping point. Economy: Early residents relied on subsistence farming, cattle raising, and trade. Cotton and corn were common crops; local ranching and the cattle trade linked the community to broader regional markets. Community institutions: A one-room schoolhouse, a church or two, and a handful of general stores anchored life in Old Bluffton. These institutions also served as social hubs for dances, meetings, and religious life.

19th century transportation and regional ties

Roads and stage routes: Before railroads reached many parts of North Texas, stagecoach and wagon roads determined which towns prospered. Old Bluffton sat near some of these routes, giving it modest importance as a supply and rest point Railroads and decline: Like many small Texas towns, Old Bluffton’s fortunes were altered by the arrival (or bypass) of rail lines. When railroads chose other nearby towns, commerce and population often shifted away from places like Old Bluffton, which limited growth.

20th century changes

Agricultural shifts: Mechanization, the boll weevil’s impact on cotton, and market fluctuations pushed many rural Texans to migrate to towns and cities. Old Bluffton’s population dropped as younger generations left for jobs elsewhere. Great Depression and war years: Economic hardship during the Depression and the draw of wartime industry and postwar opportunities accelerated rural depopulation. Remaining residents consolidated farms and adjusted to new economic realities .Preservation and memory: By mid- to late-20th century, Old Bluffton—like many small Texas settlements—was remembered for its historic buildings, cemetery grounds, and local stories rather than as a growing commercial center.

Cultural and historic legacy

Architecture and sites: The surviving structures (often a church, a few residences, and an historic cemetery) tell the story of frontier life, family ties, and community persistence. Tombstones and markers reveal family names, epidemics, veterans, and migration patterns. Oral histories: Local folklore, family recollections, and county histories preserve tales of social events, notable citizens, and everyday life. These narratives are crucial for understanding the town’s character and social fabric. Regional role: Old Bluffton is representative of many small Texas communities that sprung up in the 19th century and later diminished as economic and transportation patterns changed. It provides insight into frontier settlement, agricultural economies, and rural resilience.

Present-day

Ghost-town atmosphere: Depending on preservation and local interest, Old Bluffton may feel like a ghost town or a quiet residential community. Its remnants are of interest to historians, genealogists, and travelers who enjoy off-the-beaten-path sites. What to look for: Historic cemeteries, the footprint of old schoolhouses or churches, foundation ruins, and period fences or windmills. Conversations with county historical societies or long-time residents often yield the richest information Recommended approach: Treat sites respectfully—private property rules and historic preservation norms apply. Photograph, record stories, and check local archives for maps, deeds, and newspaper clippings to deepen your understanding.

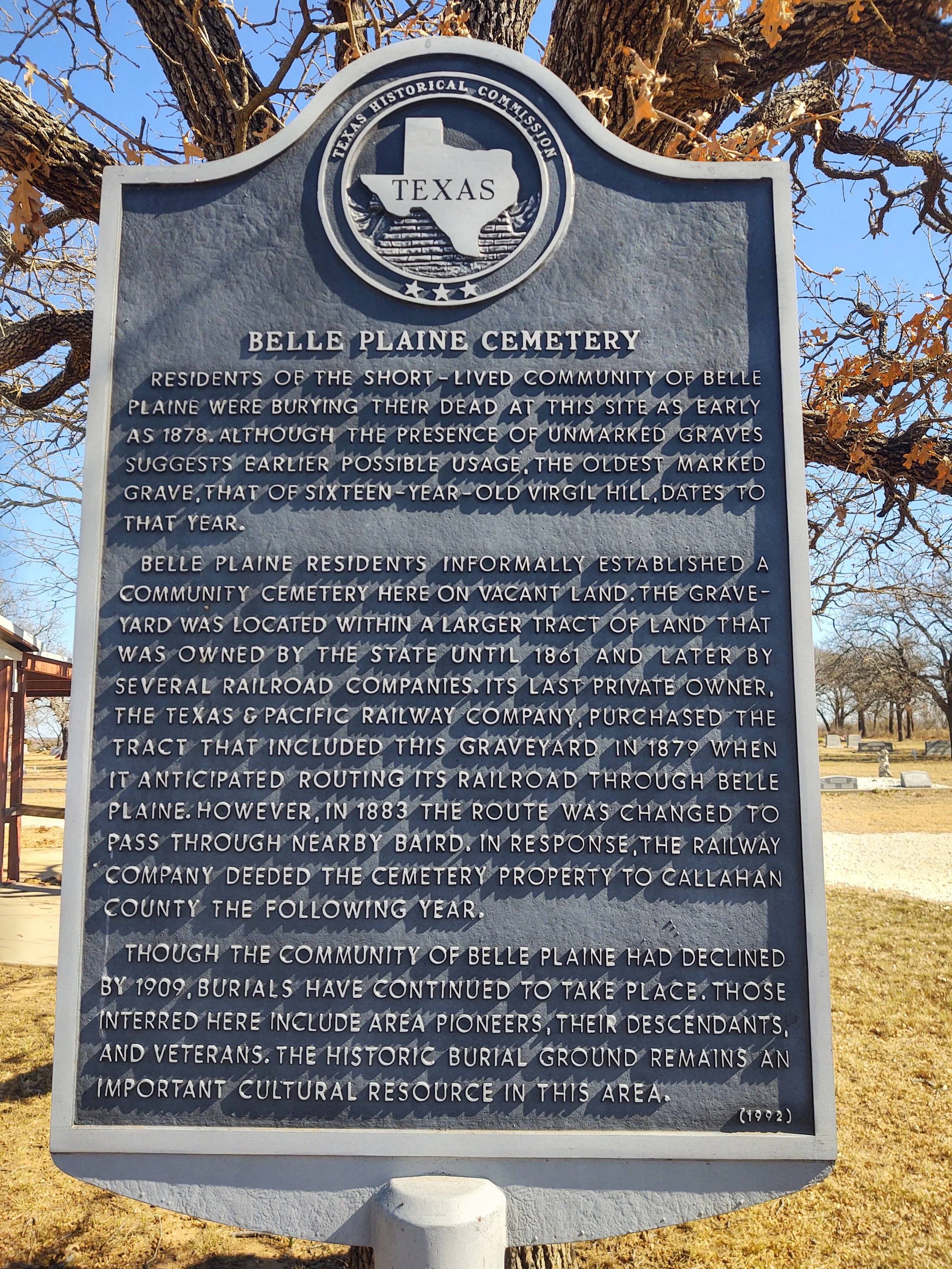

Belle Plain — ghost town, former county seat, and a snapshot of 19th-century frontier ambition — sits in Callahan County, a few miles west of present-day Abilene. Its rise and fall reflect patterns common to many frontier towns: hopeful settlement, civic prominence, disease and disaster, and eventual abandonment when railroads and political decisions shifted power elsewhere.

Founding and early growth (1850s–1870s)

The area around Belle Plain was settled in the 1850s and 1860s by Anglo-American settlers moving into central Texas after the Mexican–American War and the opening of more land for ranching and farming. The town of Belle Plain was formally established in 1876. Its name—often written as Belle Plain or Bell Plain in period sources—likely drew on romantic notions of the prairie (“plain”) and common female names used to lend a genteel image to frontier settlements. Belle Plain grew quickly because it became the county seat for newly formed Callahan County in the late 1870s. As county seat it attracted a courthouse, businesses, schools, and professional services. For a time it was a center of local government and commerce for the surrounding ranches and farms.

Civic life and institutions

The town boasted a courthouse and jail, a post office, hotels, general stores, churches, and a school—typical institutions that marked a successful county-seat town in the post‑Reconstruction era. Social life included church gatherings, public meetings, and seasonal events. The town served as a regional hub where ranchers and farmers came to trade, obtain legal services, and participate in civic affairs.

Setbacks: fire, disease, and the railroad (1880s)

Belle Plain’s fortunes began to decline in the 1880s after a series of setbacks. Disease outbreaks, particularly smallpox, struck the area and reduced the population and confidence in the town. A major turning point was the routing of the Texas and Pacific Railway (and later competing lines) through other nearby communities. When the railroad bypassed Belle Plain in favor of towns like Baird and Abilene, the economic lifeline of stagecoaches and overland supply dwindled. In 1883 a significant fire destroyed part of the town’s business district. Without the railroad and with a diminished population, rebuilding was difficult.

Loss of county seat and abandonment (late 1880s–1900s)

In 1883 the county seat was moved from Belle Plain to nearby Baird (or another growing rail town in Callahan County) — a common death knell for many 19th-century towns whose status depended on county government. With government functions gone and commerce shifting to rail towns, residents moved away to find opportunity elsewhere. Businesses closed, buildings were left to decay, and the post office eventually shut down. By the turn of the 20th century Belle Plain was largely abandoned and became one of Texas’s many ghost towns.

Today Belle Plain is a historic site rather than an inhabited town. Ruins and graves in the area mark the footprint of the settlement: foundations, old stonework, and a cemetery preserve the memory of the community that once was. The Belle Plain Cemetery is a common point of interest for historians and visitors, containing the graves of early settlers, county officials, and victims of the epidemics and hardships that accompanied frontier life. Belle Plain’s story is often cited in regional histories as an example of how disease, disaster, and railroad routing decisions determined which towns prospered and which faded away in late 19th-century Texas.

Independence, Texas — small, quiet, and rich with 19th-century Texas history — began as a frontier settlement that played an outsized role in the early Republic and Republic-era education and religion.

Founding and Republic Era

Origins: Independence sprang up in the 1830s in what would become Washington County, on land settled by Anglo-American colonists after Mexican control waned following the Texas Revolution. Its name likely reflects early settlers’ pride in Texan independence. Role during the Republic of Texas (1836–1846): Independence became an important local center for commerce, politics, and community life. The town’s location near fertile prairie and trade routes helped it attract settlers and institutions.

Religious and Educational Importance

Baylor University: The most significant chapter in Independence’s history is its connection to Baylor University. Founded in 1845 by the Republic of Texas Baptist Convention, Baylor began in Independence as Baylor University at Independence. The school served as a cradle of higher education in Texas — offering classical education, ministerial training, and civic leadership for the region. Religious Institutions: Independence hosted several Baptists churches and gatherings, reflecting the town’s importance as a religious center in mid-19th-century Texas. Reverend Samuel Wait and other Baptist leaders were central figures tied to the school and town life.

Civil War and Reconstruction

Civil War impact: Like much of rural Texas, Independence was affected by the Civil War and its aftermath. Young men left to serve in Confederate ranks; the economy and population were strained during and after the war. Postwar decline: Reconstruction-era economic shifts and transportation changes began to alter regional patterns of growth. Independence faced challenges that would later influence its fortunes.

Railroads, Relocation, and Decline

Railroads and county seat shifts: The late 19th century brought railroad expansion across Texas. Independence was bypassed by major rail lines, which tended to favor towns with better access. Nearby Brenham and other towns on rail lines grew, drawing business and government institutions away. Baylor’s moves: Baylor University’s relationship with Independence ended when the school relocated. After moving to Waco in the 1880s (following an earlier partial move to nearby towns), Baylor’s departure accelerated Independence’s population decline and loss of civic prominence. County seat: Independence lost status as a local administrative center as the region consolidated around rail-connected towns.

20th Century to Present

Historic preservation: Though the town faded as a commercial center, many 19th-century buildings, homesteads, and cemeteries remained. These structures preserved the tangible history of Texas’s Republic-era life. Cultural memory: Independence is now noted for its historical significance—especially the original Baylor campus site, churches, and gravesites. The surrounding area preserves rural West-Central Texas landscapes and the layered stories of early settlers, enslaved people, and later residents. Tourism and education: Today Independence is of interest to historians, genealogists, and visitors drawn to Texas’s early republic story. Interpretive markers, preserved buildings, and cemetery tours help tell the town’s role in education, religion, and frontier life.

The Grove — a small, unincorporated community in McLennan County — began as a rural settlement shaped by agriculture, transportation, and the tides of regional growth. Here’s a concise history highlighting the key moments and features that defined The Grove. Today the buildings stand silent offering a glimpse into what life used to be in The Grove.

Early settlement and origins

Land and settlers: European-American settlement in the area began in the mid-19th century as families moved into central Texas after Texas joined the United States. The fertile Blackland Prairie soil and access to nearby waterways made the area attractive for farming and ranching. Name: The community took its name from a prominent grove of trees near the original settlement, a common naming convention in rural Texas where groves provided shade and a meeting place for early residents.

Storefront

Saloon

19th century development

Agriculture: Like much of central Texas, The Grove was primarily agricultural. Cotton, corn, and livestock were mainstays of local production. Family farms and ranches formed the backbone of the local economy and social life. Roads and nearby towns: The Grove’s fortunes were tied to transportation routes and the growth of nearby towns. Proximity to larger centers such as Waco influenced commerce and access to markets.

20th century changes

Population and community life: Throughout the early-to-mid 20th century The Grove remained small, with community life centered on country schools, churches, and general stores. These institutions served as social hubs for the dispersed rural population. The Great Depression and mechanization: Economic shifts, including the Depression and later agricultural mechanization, reduced the need for labor on farms and prompted outmigration to cities for jobs, mirroring a statewide and national trend. Schools and consolidation: As rural populations declined, smaller community schools often consolidated with larger district schools in Waco and nearby towns, changing daily rhythms and local identity.

Sheriff’s office

Barber shop

Late 20th century to present

Unincorporated status: The Grove has remained unincorporated, meaning it has no municipal government and relies on McLennan County for services. This status preserved a quieter, rural character even as nearby urban areas expanded. Suburban influence: Expansion from Waco and the broader Central Texas growth corridor brought some suburban and exurban development pressures. While parts of the region have seen residential growth, The Grove’s core has retained much of its rural character. Heritage and community memory: Local cemeteries, churches, and historic farmsteads keep the memory of early settlers and community life alive. Residents and descendants maintain ties through reunions, church events, and local history projects.

Toyah — a tiny West Texas community with a name that hints at frontier stories and a past shaped by railroads, ranching, and oil — sits in Reeves County along the Pecos River corridor. Its history is a compact narrative of transportation booms, shifting county seats, and the tough endurance typical of small desert towns.

Early settlement and name

The Toyah region was originally inhabited by Native American groups — primarily the Apache and Comanche — who used the Pecos River corridor for travel and resources. Anglo-American settlement began in the mid-19th century as Texas expanded westward. The town’s name, Toyah, is thought to derive from an Indigenous word meaning “flowing water” or “green valley,” a reference to the river oasis in an otherwise arid landscape. Variants and spellings appear in 19th-century records.

County seat years and early growth

Toyah emerged as a local center after Reeves County was organized in 1883. The town briefly served as the county seat, a status that attracted businesses, legal activity, and settlers. In 1881–1882, a post office was established, and local ranching and farming supported the community. The Pecos River and nearby springs provided the limited water resources necessary for settlement.

Railroad era and decline

The real turning point for many small West Texas towns was the arrival (or absence) of the railroad. Toyah’s fortunes were affected by railroad routing decisions. When the Southern Pacific and other lines expanded across the region, towns that landed stations often prospered; those bypassed tended to stagnate. Toyah experienced some railroad-related activity but was overshadowed by neighboring towns that became larger rail hubs. As county services moved and commerce shifted, Toyah’s population and businesses declined.

Oil, salt, and mid-20th-century shifts

West Texas oil discoveries in the 1920s–1940s reshaped the regional economy. While Toyah itself did not become a major oil boom town, the broader Reeves County oil and mineral economy influenced employment and migration patterns. Salt deposits and other mineral resources in the area also supported extractive industries Throughout the 20th century, mechanization of agriculture, consolidation of ranch lands, improved highways, and urban migration reduced rural populations. Toyah’s numbers dwindled; by mid-century it was a small, quiet community.

Modern Toyah

In recent decades Toyah has remained an unincorporated community with a very small population. It sits along Interstate 20 (formerly U.S. Route 80), which brings occasional travelers, truckers, and those exploring West Texas deserts and historic routes. Surviving structures, cemetery markers, and periodic local memory keep the town’s story alive. Toyah today is emblematic of many small West Texas settlements: modest, rooted in a landscape of wide skies and sparse water, and layered with frontier, ranching, and oil-era history.

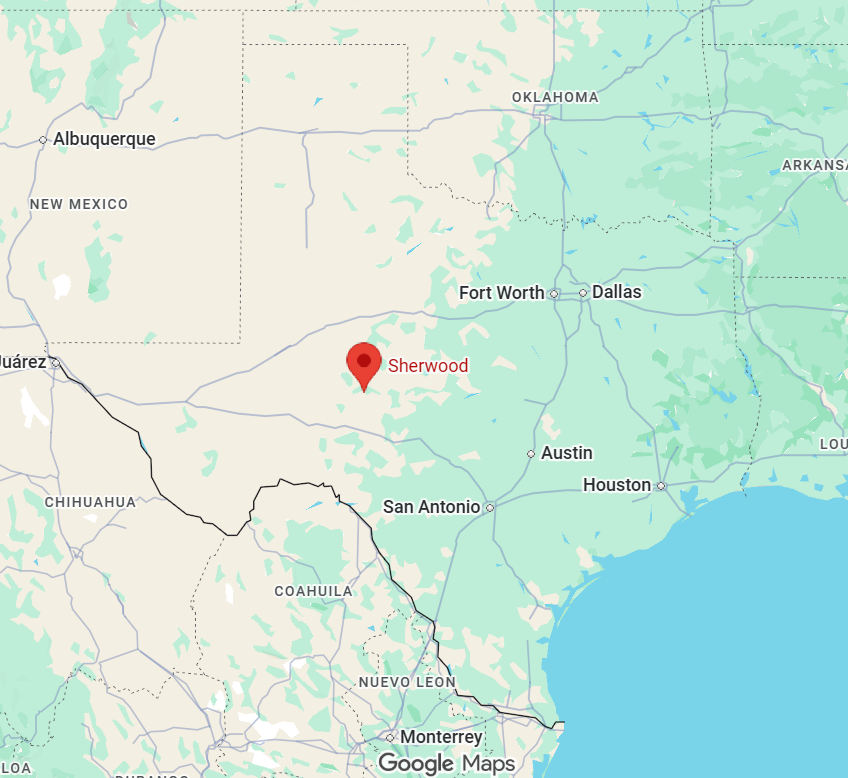

Sherwood: Served as the Irion County seat until 1939 and still features its historic courthouse. Sherwood, Texas — a small town with a quiet present and a layered past — sits in East Texas, shaped by timber, railroads, and the ebb and flow of rural life. Its history reflects common themes of the region: Indigenous presence, European settlement, the rise and decline of resource industries, and the resilience of local communities.

Early inhabitants and land

Indigenous peoples: Before European settlement, the area that became Sherwood was part of the broader homeland of several Native American groups who hunted, fished, and traveled through East Texas. By the 18th–19th centuries, many Indigenous communities had been pushed westward or assimilated as Anglo and African American settlers expanded into the region. Land grants and early settlement: Like much of East Texas, the land entered Anglo-American records through Mexican and then Texan land grants. Early settlers were attracted by fertile soils, pine forests, and streams that supported small-scale farming and homesteads.

Timber and the rise of the town

Pine forests and the lumber industry: Sherwood’s growth was closely tied to East Texas’s vast pine forests. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, logging companies moved into the region, building sawmills and cutting rail spurs. Towns like Sherwood sprang up around mills, railroad stops, and timber camps. Railroad influence: Rail lines were crucial to Sherwood’s development. Railroads carried lumber, agricultural products, and later people, linking Sherwood to regional markets and enabling modest commercial growth. A depot or rail siding often served as a focal point for these small timber towns.

Community life and institutions

Agriculture and livelihoods: Aside from timber, residents farmed cotton, corn, and raised livestock. A mixed economy of sawmills, small farms, and local trades sustained the community through the first half of the 20th century. Churches, schools, and civic life: Like most rural Texas towns, Sherwood developed churches, a schoolhouse, general stores, and civic organizations that anchored community life. These institutions served as social hubs, hosting events, meetings, and fairs.

20th century changes

Boom-and-bust cycles: Sherwood experienced the classic boom-and-bust pattern tied to natural-resource extraction. As timber was harvested and mills closed or consolidated, employment declined. Mechanization and larger industrial centers further drew jobs away. The Great Depression and postwar era: Economic hardship in the 1930s affected Sherwood’s families, as it did across rural America. After World War II, population shifts—young people moving to cities for work, improved transportation, and changing agriculture—further reduced the town’s size and economic base.

Quick timeline

Pre-1800s: Indigenous presence across East Texas.

1800s: Anglo settlement increases; land grants and homesteads established.

Late 1800s–early 1900s: Timber industry booms; sawmills and railroads spur town growth.

1930s: Economic hardship during the Great Depression.

Mid–late 1900s: Decline in local mills and population as industry consolidates; migration to cities.

2000s–present: Small-community resilience, heritage preservation, and rural lifestyle continue.

What remains to explore

Cemeteries and churches: For those researching local history, small-town cemeteries, church records, and school rosters often reveal family ties and migration patterns. Oral histories: Longtime residents and descendants of early settlers can provide anecdotes and details missing from official records—stories about mill life, harvest seasons, and community gatherings. Physical remnants: Foundations, abandoned mill sites, old railroad grades, and historic homes offer tangible links to Sherwood’s past.

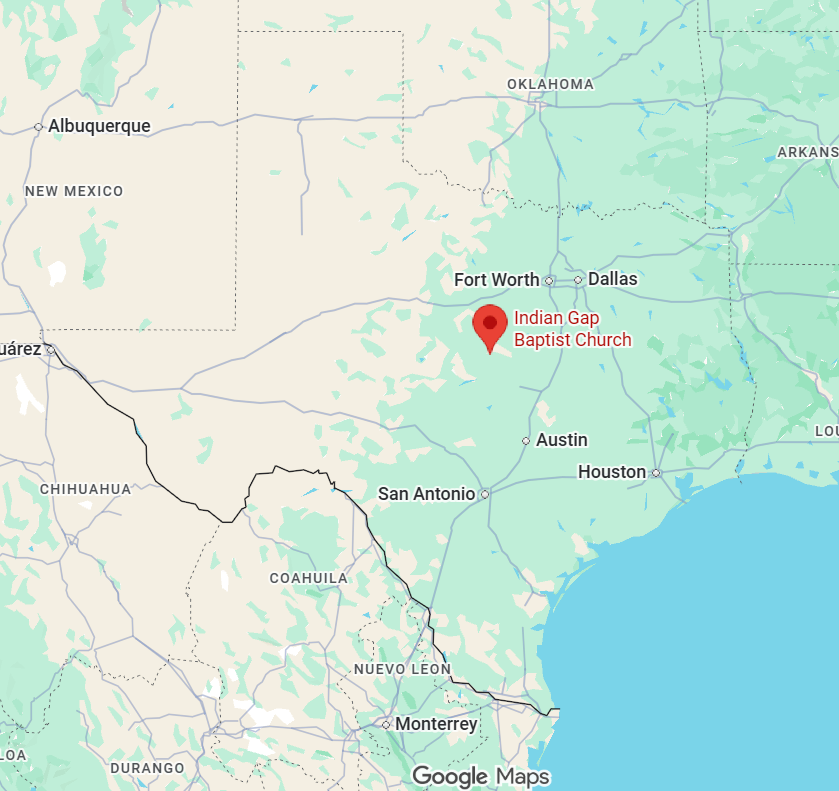

Indian Gap — tiny, tucked-away, and woven into the wide tapestry of Central Texas history — is one of those small places that carries a surprising depth of story. Located in Hamilton County, roughly midway between the larger towns of Hamilton and Brownwood, Indian Gap has roots in Native American travel routes, 19th-century settlement, frontier life, and the quiet persistence of rural Texas communities.

Early history and name

The name "Indian Gap" likely comes from a natural low point or pass in the surrounding hills that Native American groups used as a travel corridor. Before Anglo settlement, the area was traversed by Tonkawa, Comanche, and other tribes who used local springs, rivers, and gaps as routes for hunting, trade, and seasonal movement. As Anglo-American settlers moved into Central Texas after Texas independence (1836) and especially after the Civil War, these natural corridors became roads for settlers, cattle drives, and later stage and mail routes.

Settlement and 19th-century life

Settlement in the Indian Gap area accelerated in the latter half of the 19th century. Ranching and small-scale farming were the economic backbone. The region’s rolling limestone hills and grasses supported cattle and horses, and families built homesteads and small communities around schools, churches, and stores. Like many small Texas settlements, Indian Gap developed civic and social institutions that anchored the community: a post office, country stores, a schoolhouse, and churches. The post office often served as a community hub; Indian Gap had its own post office for periods during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

20th century: change, consolidation, and rural persistence

The 20th century brought both continuity and change. Mechanized agriculture, improved roads, and economic shifts led many small rural communities to consolidate: schools combined, farmers adapted or left for towns, and smaller stores closed as residents traveled farther for goods and services. Despite these changes, Indian Gap remained a locus for local ranching families and community life. The school and churches that survived helped maintain social ties. Population numbers remained small but stable enough to preserve the identity of the place.

Notable landmarks and community

Indian Gap is known locally for its community cemetery and for historic homes and ranches in the surrounding countryside. These sites reflect the long presence of families whose histories are interwoven with the land. The area’s landscape — limestone outcrops, cedar and live oaks, and wide ranchlands — underscores the rural Texas character felt across Hamilton County.

Present day

Today Indian Gap remains an unincorporated, rural community. It does not have the services or population of a larger town, but it continues as part of Hamilton County’s network of ranches, family properties, and country roads. Visitors interested in Texas rural history, genealogy, or quiet landscapes can find Indian Gap representative of many such small Central Texas communities — places where the past is visible in cemeteries, old homesteads, and the names of local features on maps.

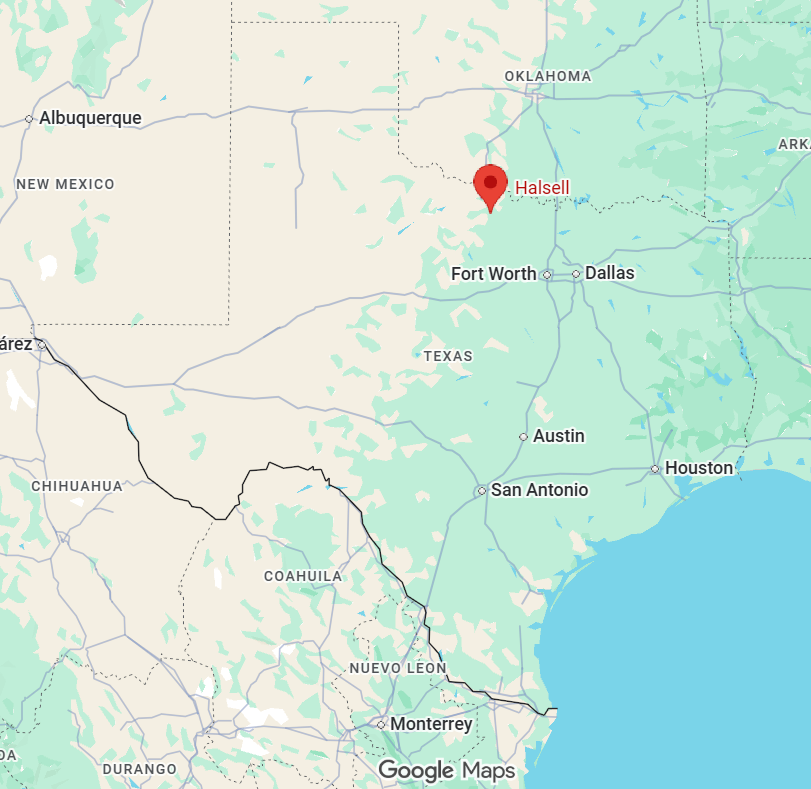

Halsell — a tiny, nearly-forgotten dot on the map — sits in north-central Clay County in northwest Texas. Its history is a snapshot of early 20th-century rural America: tied to ranching, railroads, oil dreams, and the slow ebb of small-town life.

Founding and name

Halsell grew from ranching roots in an area originally occupied by Caddo and other Indigenous peoples before Anglo settlement. The town was named for either A. H. Halsell, a prominent rancher and landowner, or a Halsell family connected to regional development (naming sources vary). The Halsell name was associated with local land and cattle operations that shaped settlement patterns.

Railroad and early growth

Halsell’s growth was linked to railway expansion and local agrarian commerce in the early 1900s. Rail lines and nearby roads helped move cattle, cotton, lumber, and farm goods, giving rise to small service points and post offices that anchored rural communities. By the 1910s–1920s the community had enough population and businesses to be noted on county maps and in postal directories. Typical facilities included a post office, general stores, and services supporting ranchers and farmers.

Oil era and economic shifts

Like many North Texas communities, Halsell felt the ripple effects of oil discoveries in the region during the 1920s–1940s. Nearby oil booms brought temporary workers, speculation, and sometimes modest local gains in commerce and population. However, Halsell never grew into a boomtown. Its economy remained broadly agricultural and ranch-focused. Over mid-century decades, mechanization, consolidation of farms and ranches, and population migration to larger towns and cities slowly reduced the town’s permanent population.

Post office, decline, and legacy

The Halsell post office was a key marker of the town’s official status; as rural post offices closed or consolidated in the mid-20th century, many small places like Halsell faded from routine use. By the latter half of the 20th century and into the 21st, Halsell became best described as a crossroads or dispersed rural community rather than an incorporated town — a handful of homes, ranches, and historical traces on county maps. Today Halsell’s legacy is preserved in local histories, county records, and the memories of families tied to the land. It’s representative of countless small Texas settlements whose stories reflect ranching culture, the modest impact of oil booms, and the gradual centralization of commerce and population in larger regional centers.

Halsell today

Halsell is a lens on rural Texan life: how landscape, cattle, rail lines, and resource booms shape settlement; how small communities rise and recede; and how local names persist in maps, cemeteries, and legal records even when storefronts and post offices vanish. For travelers and history seekers, places like Halsell offer quiet insight into everyday frontier and agricultural histories away from the flash of big-city museums — perfect for road trips focused on regional memory, historic ranching culture, and the layered human geography of North Texas.

Barstow — small town, big story. Nestled in west-central Texas in Ward County, Barstow’s history is a patchwork of ranching, railroads, oil booms, and resilient small-town life.

Early settlement and ranching

The land around present-day Barstow was originally part of expansive ranchlands in the 19th century. Anglo-American settlement increased after the Civil War as cattle ranching spread across West Texas. Large cattle drives and open-range grazing defined the region’s economy and culture in the late 1800s. Ranch families and cowboys shaped local place names and patterns of land use. Sparse settlement, dusty trails, and the rhythms of seasonal ranching characterized life before formal town development.

Railroad and town founding

Barstow formed as a town in the early 20th century when the Texas and Pacific (and later other rail lines) expanded through the area. Rail access was a crucial factor in founding many West Texas communities: it provided a way to move cattle, goods, and people and often determined which locales grew into towns. The town was platted and named during this era; local lore and records tie the name “Barstow” to either railroad officials, early settlers, or borrowed names from other towns. As tracks and a depot appeared, Barstow became a stop for freight and passengers and a service center for surrounding ranches.

Agriculture, cotton, and community life

With railroad connections, agriculture expanded. Cotton, a major Texas crop of the early 20th century, was important in the surrounding county alongside continued cattle ranching. Farming communities clustered around towns like Barstow for supplies, markets, and social life. Churches, schools, general stores, and a courthouse in nearby smaller towns anchored daily life. Community events, school sports, and church gatherings were central to social life.

Oil, economic cycles, and the 20th century

West Texas oil discoveries in the 20th century transformed many small towns. While Barstow was not a major oil city like some regional centers, petroleum development in Ward County and surrounding areas affected local employment and prosperity in boom periods. Like many rural Texas towns, Barstow experienced the ups and downs of agricultural prices, the Great Depression, mechanization of farming, and rural-to-urban migration. These trends reduced population in many small towns while reshaping local economies.

Recent decades and character today

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, Barstow has remained a small, tight-knit community. Population has been modest; the town serves local ranching and farming families and functions as a waypoint on regional roads. The town retains elements of classic West Texas small-town life — local businesses, community gatherings, and a landscape that reflects its ranching and agricultural roots. Barstow’s history is less about grand monuments and more about everyday resilience: people maintaining livelihoods on challenging land, adapting through economic change, and keeping community ties alive.

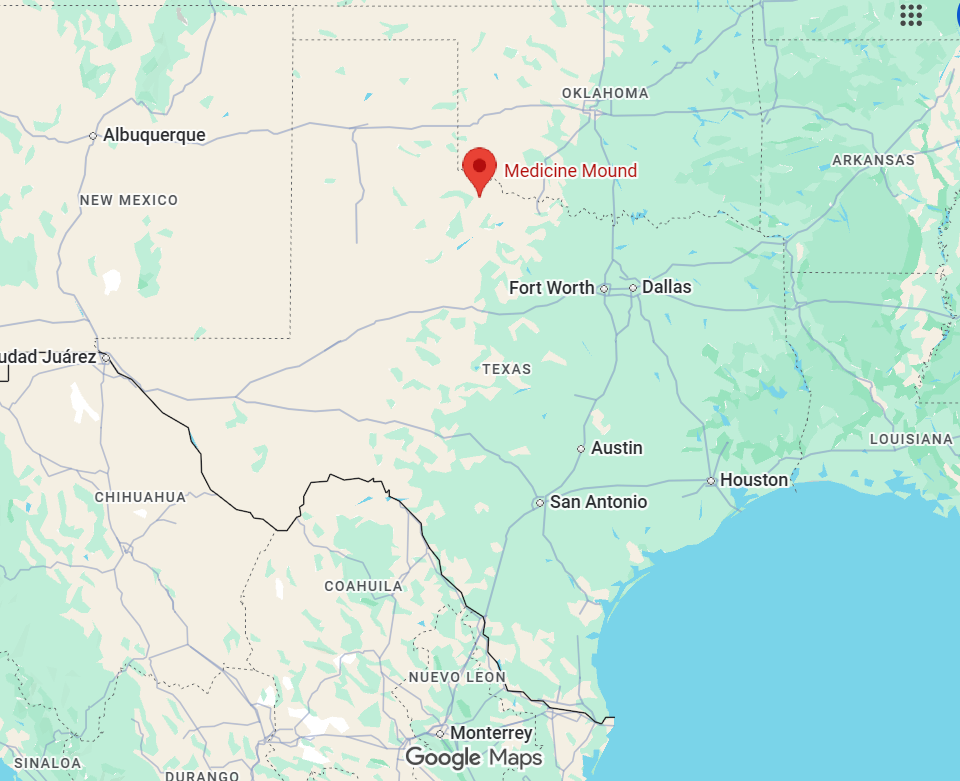

Medicine Mound — a small, unincorporated community in Runnels County — carries a history tightly woven with frontier life, Native American lore, and the slow rhythms of rural West Texas. Its story reflects common themes of settlement, native displacement, ranching, and the importance of place-names tied to landscape and legend.

Origins and name

The name "Medicine Mound" likely derives from a distinctive natural rise or hill used by Indigenous peoples for medicinal or ceremonial purposes. "Medicine" in place names commonly denotes a site believed to possess healing powers or spiritual significance. Before European-American settlement, the region was part of the broad territory used seasonally by Kiowa, Comanche, Tonkawa and other Plains tribes. They followed bison and used local springs and landmarks — like mounds — as gathering and ritual places.

Settlement and 19th-century life

Anglo-American settlement in the area accelerated after Texas statehood and especially after the Civil War. In the late 1800s, ranching and cattle drives shaped much of Runnels County’s economy and settlement pattern. Small communities such as Medicine Mound formed around ranches, water sources, and stage or wagon routes. These stops offered supplies, social contact, and mail service to widely dispersed ranching families. Conflict and tension between Native groups defending territory and incoming settlers continued into the late 19th century, as it did across much of West Texas, until the power of Plains tribes was largely broken by military campaigns and the decline of the bison.

20th century: post office, school, and decline

Like many rural Texas hamlets, Medicine Mound gained formal recognition when it acquired a post office and a school. The establishment of a post office often marked a settlement as an official community and tied it into regional communication and commerce networks. Rural schools served as educational, social, and civic centers for the surrounding farming and ranching families. They were essential to maintaining community identity. Over the 20th century, mechanization of agriculture, consolidation of ranches, the Great Depression, and the draw of urban jobs caused population decline in many small West Texas communities. Schools consolidated into larger districts and local post offices closed; Medicine Mound’s role as a standalone town diminished.

Visiting today

Visiting the Medicine Mound area is an exercise in reading landscape: looking for old fences, stone foundations, cemetery markers, and natural features that hint at stories from the past. Because the site and surrounding land are often on private ranches, respect for property and local residents is essential. Runnels County historical resources and local historians can guide interested visitors to publicly accessible sites and archival materials.

Bottom line Medicine Mound, TX, is less a single dramatic event than a capsule of frontier-era patterns: indigenous significance of place, settlement around water and ranching opportunities, the establishment of minimal civic institutions (post office, school), and gradual decline as rural America consolidated. Its name preserves a whisper of Indigenous spiritual geography even as the physical community has largely faded into the West Texas plain.

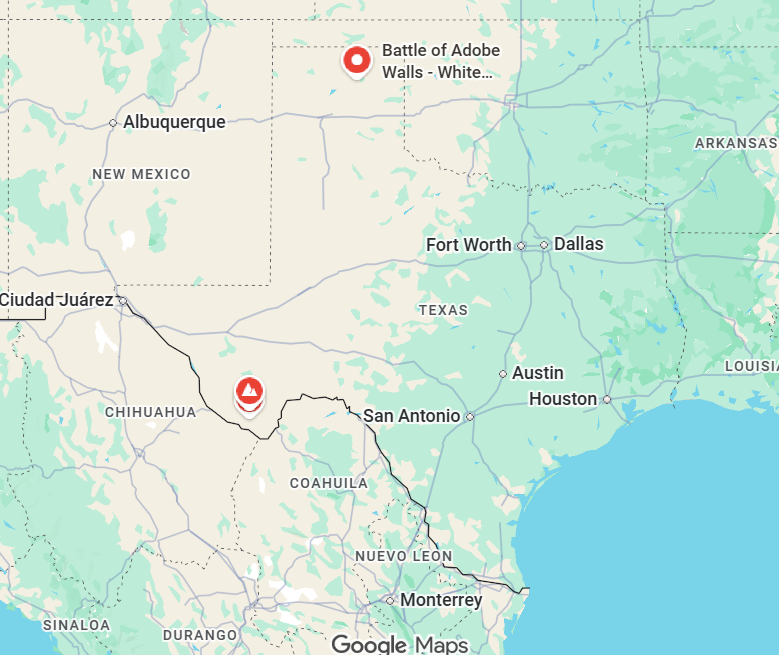

Adobe Walls — Adobe Walls is best known for two pivotal battles between Native American tribes and European-American buffalo hunters/settlers on the Texas plains. The name comes from the adobe brick ruins at a trading post and the later fortified trading post built near them. Adobe Walls sits in the Texas Panhandle region and played a key role in the late 19th-century conflicts that shaped the American West.

Early site and name

The original Adobe Walls were built in 1843–1844 by Bent, St. Vrain and Company as a trading post called Bent’s Fort—often referred to locally as Adobe Walls because of its thick adobe (sun-dried mud brick) walls. That earlier post served travelers and trappers on the High Plains and traded with Plains tribes. Over time the name “Adobe Walls” came to refer to the general area where adobe structures were visible on the otherwise treeless plain.

First Battle of Adobe Walls (1864)

Date and combatants: November 1864. This clash took place during the Civil War era and involved Plains Indian fighters—mainly Kiowa and Comanche—attacking a small group of buffalo hunters and traders at the old trading post ruins. Context: Tensions rose as more hunters and settlers encroached on bison herds and tribal hunting grounds. The first battle was part of a broader pattern of contest for resources and retribution for raids and killings on both sides. Outcome: The Native force routed the small group of defenders, reinforcing tribal resistance against continued incursions. The encounter discouraged temporary settlement at the site for some years.

Second Battle of Adobe Walls (1874)

Date and combatants: June 27, 1874. This larger, better-documented fight pitted a band of about 28 white and Mexican hunters and traders—famed buffalo hunters such as Andrew “Buckskin” (William) and Billy Dixon—against a coalition of hundreds of Plains warriors, primarily Comanche, Kiowa, and Cheyenne, led by war leaders including Quanah Parker and Big Red Meat. Causes: The immediate cause was continued commercial buffalo hunting, which decimated bison herds crucial to Plains tribes’ economy and culture. The hunters at Adobe Walls had also been reporting encroachments and retaliatory raids across the plains. The battle: The Native coalition launched a major assault on the fortified trading post. Despite overwhelming numbers, the hunters held out, using the post’s higher ground, long-range rifles and some artillery. One famous incident was Billy Dixon’s long-range shot, which was reported to have struck a Native warrior at extraordinary distance—an event later embellished in legend. Outcome and significance: Although the attackers were not decisively defeated, they failed to dislodge the defenders. The Second Battle of Adobe Walls signaled the last major large-scale Native offensive in the Southern Plains. Its aftermath helped prompt the Red River War (1874–1875), a military campaign by the U.S. Army that forcibly moved Plains tribes onto reservations and effectively ended large-scale resistance in the region.

Aftermath and legacy

Military and cultural consequences: The struggle at Adobe Walls accelerated the destruction of the bison and the collapse of the Plains tribes’ free-ranging lifeways. Military campaigns that followed led to confinement of tribes to reservations in Oklahoma and elsewhere. Commemoration and site history: The Adobe Walls battlefield area later attracted interest from historians, archaeologists, and tourists. The adobe ruins and later monuments commemorate the clashes. The area today is privately owned in parts and has been subject to preservation efforts and archaeological study. Myth and media: Stories out of Adobe Walls—especially tales of long-distance rifle shots and heroic stands—have entered Western folklore. Figures like Quanah Parker, Billy Dixon, and others became prominent in both tribal memory and frontier lore.

Visiting and interpreting Adobe Walls today

The battlefield and associated sites are studied and interpreted variably; some markers, memorials, and museum exhibits highlight military history and buffalo hunting lore, while Indigenous perspectives emphasize dispossession and cultural loss. For visitors interested in dark tourism and historical layers: Adobe Walls offers a stark example of frontier violence, ecological collapse, and the human costs of expansion—an appropriate stop for those exploring the deeper, often uncomfortable histories of the American West.

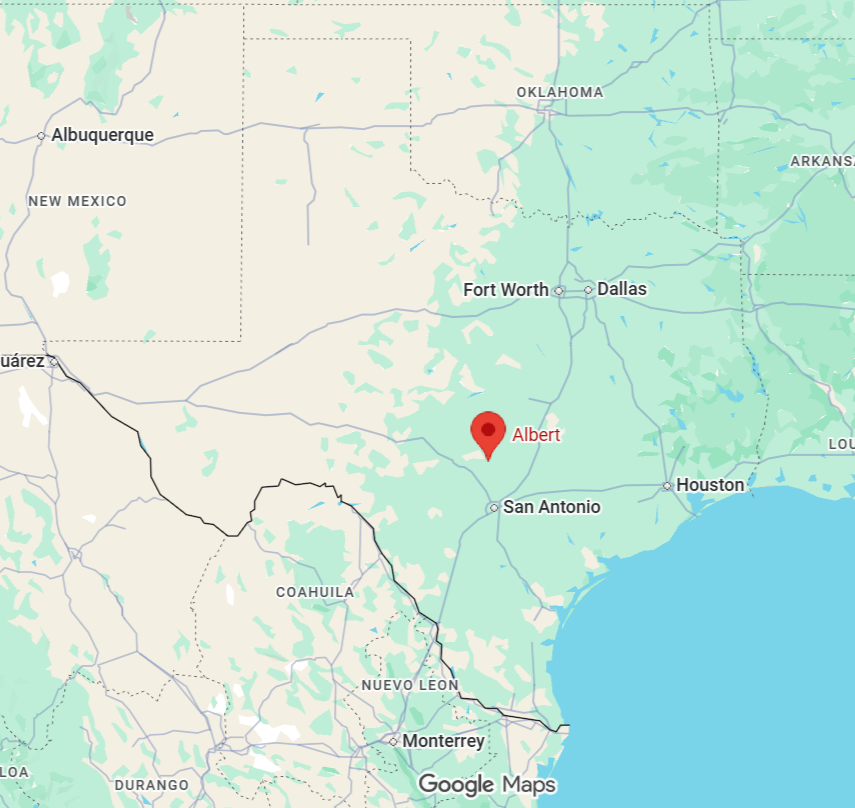

Albert — a tiny, almost-forgotten community in Parmer County on the High Plains of the Texas Panhandle — has a history that’s quietly tied to the railroad, farming transformation, and the steady outflow that reshaped many rural American towns in the 20th century.

Early settlement and railroad origins

The area that became Albert was part of the vast XIT and other large ranching and open-range tracts that dominated the Panhandle after Civil War-era settlement. Like many Panhandle communities, its formal birth is connected to the arrival of the railroad. Albert began as a railroad siding and stop on the Pecos Valley and Northern Texas Railway (later part of larger rail systems) in the early 20th century. Rail lines were crucial here: they brought settlers, supplies, and a way to ship grain and cattle to market.

Agriculture and community life

The town’s economy centered on dryland farming and later irrigated agriculture. The High Plains’ flat land and, after windmills and then irrigation wells, more reliable water, made the region productive for wheat, sorghum, cotton, and cattle. Small-town institutions — a post office, a school, general store, and churches — marked Albert as a local hub for nearby farms during its peak years. School consolidation later drew children to larger nearby towns, a common pattern across rural Texas.

Rail decline and population shifts

As highways improved and trucking took over freight, many small rail-dependent towns declined. Albert was no exception. Reduced rail service, combined with agricultural consolidation (farms becoming larger and fewer residents needed), led to steady population loss. Over the mid- to late-20th century, many residents moved to larger towns and cities in the region for jobs, education, and services. Small businesses closed, and some buildings fell into disuse.

Present day and legacy

Today Albert exists more in maps and memory than as a bustling place. It’s one of many unincorporated Panhandle communities that tell the story of settlement tied tightly to railroads and farming, and of later decline driven by mechanization and urban migration. The legacy of Albert is typical of rural West Texas: a reminder of how transportation networks and agricultural technology shaped settlement patterns, and how those same forces — when they changed — reshaped lives and landscapes.

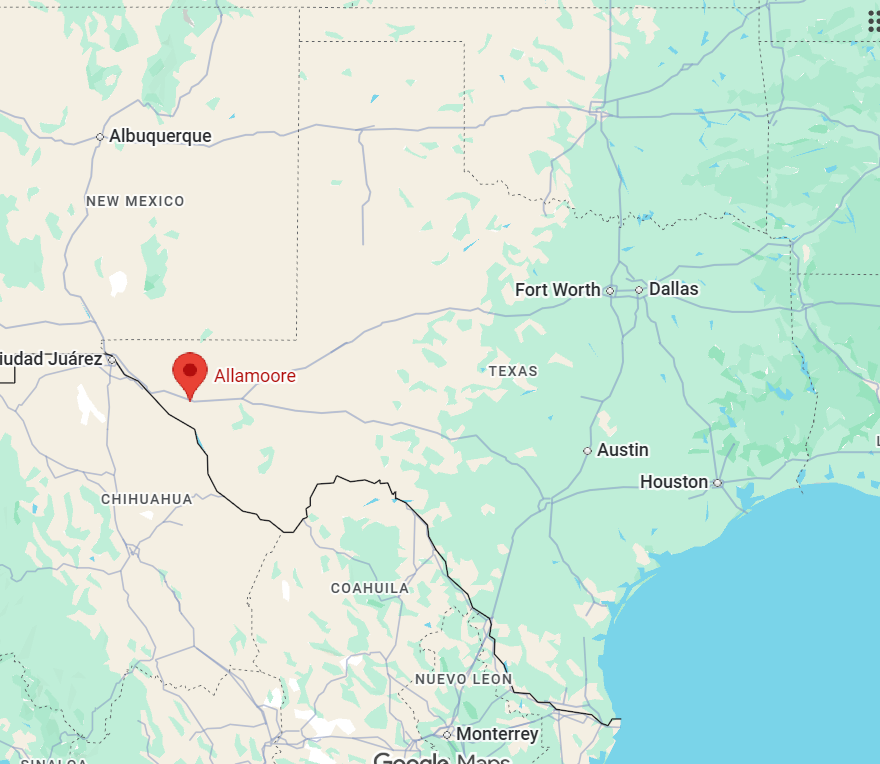

Allamoore — a tiny, wind-swept dot in Hudspeth County — has a history shaped by frontier hardship, ranching resilience, and the quiet persistence of a community on the edge of the Chihuahuan Desert.

Early inhabitants and landscape

Long before Anglo settlement, the region was part of the traditional lands used seasonally by Indigenous peoples, including Mescalero Apache bands. The harsh but resourceful desert environment supported hunting and gathering and occasional trade routes across the Trans-Pecos. The landscape — high desert plains, creosote, agave, and distant mountain ranges — defined settlement patterns: sparse, spread-out ranches and water-driven lifeways where springs, tanks, and wells dictated where people could live and herd cattle.